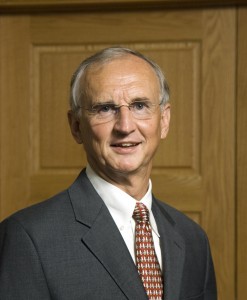

In taking the job to turn around the Connecticut State University system and the state”™s community colleges, new Board of Regents President Robert Kennedy is running into angst, uncertainty and even disbelief.

The Maine import thinks he will make believers out of tough critics here, including students, employers ”“ and even faculty.

“I may have been among the first to use the word ”˜angst,”™” Kennedy admitted, while appearing last month before a committee of the Connecticut General Assembly. “There was concern, I think, with this reorganization in a lot of different quarters, and a lot of uncertainty and unknown, and that”™s to be expected.

“One of the first meetings I had was, within the first couple of weeks when I had arrived in Connecticut, getting the 17 campus presidents together,” Kennedy said. “That was the first time that the 17 presidents had ever been in the same room together, and quite literally, some didn”™t know one another from a different campus. That alone is going to have a major effect on getting cooperation across these very good institutions, but all within their own silo.”

Kennedy previously led the University of Maine, where he said one of his proudest achievements was creating an innovation center to help students, faculty and staff explore entrepreneurial and business development ideas.

“The technology transfer effort at the university was cited by the director of the U.S. Patent Office as one of the most innovative places in the nation, and the best program that he had seen at any university,” Kennedy said.

In Connecticut, the innovation process starts with just getting kids to the graduation day podium. Just 19 percent of the full-time, first-time students entering a Connecticut State University campus graduated within 4 years; and only 46 percent of those students had their degree within six years.

The numbers at community colleges are bleaker yet. Just 3 percent of students entering full time finished their degree within two years and only 16 percent within four years. Those figures, however, include students who transfer to other schools before completing their degree, an “underappreciated” statistic, according to Kennedy, and he is counting on the Charter Oak State College online program to help lift those statistics further.

In early meetings with the Board of Regents, Kennedy has indicated he is focused on the following priorities:

Ӣ students should enter college prepared;

Ӣ students and faculty should be spurred to innovate, and learn and teach in settings that foster entrepreneurialism; and

”¢ students should benefit from enhanced collaboration and partnerships between the state”™s higher education system and the private sector.

Already, however, some faculty say Kennedy is moving too fast in attempting to install a seamless transfer process between community colleges and state universities.

“The idea that we could implement a plan for the five biggest majors ”¦ by July, which really means late April ”¦ beggars belief,” said Jason Jones, a professor at Central Connecticut State University and a chapter head of the American Association of University of Professors. “Piloting the program with the largest majors, which have many subprograms and complex accreditation demands, in ten weeks or less is a recipe for disaster.”

Louise Feroe, Connecticut State University”™s interim vice president, admitted the regents are running into resistance.

“It is that timeline that we”™ve gotten the most pushback on,” Feroe said. “I have no doubt that there will be changes to this timeline as we hear from the people who will be charged with actually doing it. What I think they don’t want to let slip ”¦ is the bottom line, the end point. By the end of the coming school year this will be complete, public, on the Web, transparent to students.

“There will be roadblocks; it”™s going to be a difficult journey,” Feroe said. “There are going to be a lot of hard conversations.”