Former College of New Rochelle controller Keith Borge ”“ who failed to pay $20.4 million in payroll taxes, caused losses of $612,398 in a securities fraud and filed financial statements that inflated college assets by $33.8 million ”“ blames the closing of the 115-year-old Catholic college on other administrators and the board of directors.

Former College of New Rochelle controller Keith Borge ”“ who failed to pay $20.4 million in payroll taxes, caused losses of $612,398 in a securities fraud and filed financial statements that inflated college assets by $33.8 million ”“ blames the closing of the 115-year-old Catholic college on other administrators and the board of directors.

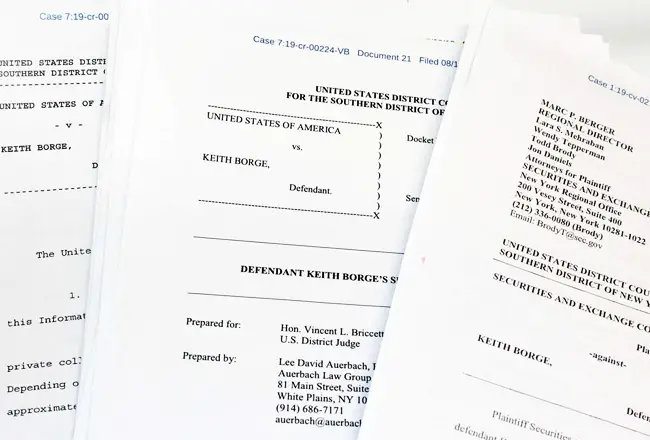

Borge detailed his version of the college”™s decline in a sentencing memorandum and letter to a federal judge in which he asks for no jail time and no fine when he is sentenced on Aug. 28.

“Yes, Mr. Borge played a role in the demise of CNR, and he deeply regrets his actions,” his attorney, Lee David Auerbach states in the sentencing memo.

“But he did not act alone. Mr. Borge appears to be the scapegoat, the tragic mascot, for the many who refused to say what their eyes were clearly able to see. He has pled guilty for the many who failed in their responsibilities and were unable to provide Mr. Borge with the financial resources he needed to satisfy CNR”™s tax obligations.”

Borge expresses regrets for his actions but claims that a sharp drop in tuition payments from declining enrollments was the primary cause of the college closing.

However, Borge is to be sentenced for criminal culpability, not for causing a college closure.

CNR”™s last class graduated in the spring and its last day of classes was this month. The 15.5-acre campus is up for sale, and Mercy College has agreed to accept CNR students as transfers. In addition, Mercy College is leasing three of CNR’s campuses, the main campus as well as the Rosa Parks campus on 125th street near the Apollo Theater in Harlem and the campus in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn.

Borge, 62, of Valley Cottage held several finance positions during his 37-year tenure. He retired in 2016. College President Judith Huntington resigned a few months later.

A forensic accountant and law firm hired by the college discovered $31.2 million in unpaid bills. Their findings were turned over to the U.S. Attorney”™s Office.

In March, Borge pleaded guilty to criminal charges of securities fraud and failure to pay payroll taxes.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission accused him in a civil suit of using the college”™s endowment to pay operational expenses without approval by the board of trustees, concealing tax obligations from college officials, and misrepresenting assets and liabilities on financial statements that deceived investors in bonds issued by the college.

Last month he consented to being assessed a civil penalty in the SEC case.

His sentencing memo and letter to U.S. District Judge Vincent Briccetti claim that college officials, including Huntington and the board of trustees, were aware of the unpaid payroll taxes and unpaid bills.

The documents do not say much about the specific actions on which the criminal and civil charges are based.

The real issue, according to Borge, is that CNR did not enroll enough tuition-paying students to support operations.

“It was simply the college”™s inability to produce enough cash,” the sentencing memo states, “that caused Mr. Borge to commit the charged offense.”

Borge also attributes CNR’s financial woes to fundraising shortfalls, building a wellness center that increased debt by $28 million, expensive leases for campuses in New York City, and programs and degrees that did not attract students.

“Where was the sense of urgency on behalf of the board and administration?” his letter asks. “For a group of intelligent people, it”™s hard to believe they couldn”™t realize the seriousness of the situation.”

The sentencing memo depicts Borge as a heroic figure who made a poor decision, “a man whose whole adult working life was spent towards the betterment of the College of New Rochelle, its students and faculty.”

Borge claims that his only motive was to help the college survive, “so that students could graduate and employees could be paid while the administration worked on things getting better.”

His letter is a litany of yes ”¦ but defenses.

Yes, he is sorry for not paying the taxes, “but the stress I was experiencing trying to keep the college open was overwhelming.”

Yes, he knew the seriousness of not paying taxes, “but the college didn”™t have the cash.”

Yes, he should have done things differently, “but I cannot change the past.”

Yes, he should have called the IRS, “but the IRS also could have contacted the college at any time.”

CNR closed its doors because enrollment dropped significantly and it was no longer an economically viable educational institution, the sentencing memo states.

“It had suffered from a fatal case of insufficient cash flow, as well as an administration who turned a blind eye to its economic demise and a board that was uninvolved.”

Nonbinding federal sentencing guidelines call for a prison sentence of eight to ten years and a fine of $30,000 to $300,000, according to a criminal plea agreement he signed in March. A pre-sentence investigation report recommended imprisonment of four years.

The U.S. Attorney”™s Office has not yet submitted its analysis and recommendations.

In asking the court for leniency, Borge and his lawyer argue that he did not personally profit from the crimes and he has no history of antisocial behavior or prior crimes, “not even a traffic ticket.”

He is a religious man, an outstanding father and husband, the principal family caregiver, the sentencing memo states. He has fully cooperated with investigators and he has taken full responsibility for his actions.

“Let me contribute to my community rather than be incarcerated,” Borge says in his letter to the judge.

“I know I had to plead guilty to these charges because of my responsibility,” he states, “but please know I was trying to keep the college going, to keep its doors open.”