Over the past few years, the use of crowdfunding platforms to attract investors for the financing of commercial real estate developments has increased, both on popular websites such as GoFundMe and Kickstarter and on standalone online resources aimed exclusively at investors pursuing real estate projects.

The union of crowdfunding and commercial real estate investment saw a major boost with the Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act of 2012, which gave federal approval for the use of crowdfunding to raise capital for enterprises. Prior to the JOBS Act legislation, real estate crowdfunding was limited to accredited investors ”“ defined by federal standards as those with an individual annual income above $100,000 or a net worth exceeding $1 million ”“ but the enactment in 2015 of Title IV of the JOBS Act, also known as Regulation A+, allowed anyone to put their money into this vehicle.

“For investors, this offered access to investment opportunities all across the U.S., across a variety of asset classes,” said Brian Esquivel, director of commercial equity for San Francisco-based RealtyShares Inc. “Historically, it was very difficult to have access to this.”

While platforms and projects vary, “The lion”™s share of investments involves buying an asset where there is an opportunity to renovate or lease up with the intention of stabilizing the asset and exiting in three to seven years,” Esquivel said.

Charles Clinton, co-founder and CEO of New York-based Equity Multiple Inc., noted that his company”™s crowdfunding outreach operates in a similar manner. “We form a single property entity as an LLC and pool the investor capital together,” he said. “That entity invests in a property. Ultimately, upon a capital event ”“ more often than not, the sale of property ”“ the investors earn back their cash yield and then a portion of sale proceeds.”

Despite a lack of data on the exact size of the real estate crowdfunding market in the U.S. ”“ no federal agency or national trade association tracks those deals – the investment vehicle apparently is attracting a particular class of investor.

“This investor is typically younger,” said Ben Sayles, director in the Boston office of real estate brokerage HFF. “From what I am seeing, this person is high-earning, usually in the tech world ”“ though maybe in the financial world ”“ and doesn”™t have a lot of expenses. They probably rent their apartment, do not have a car and have an extra income that they want to put to work.”

Among real estate professionals, the use of crowdfunding to raise capital also appears to be concentrated within a particular demographic.

“For a smaller commercial real estate developer or investor, the non-Donald Trump type, this can be a cheaper source of financing for a $10 million to $30 million project,” said professor Anthony Macari, executive director of graduate programs at Sacred Heart University in Fairfield.

Macari envisioned crowdfunding as a potential tool for growing the commercial property markets in smaller cities. “There are some areas that need development and commercial real estate investment but are not necessarily able to attract biggest and best players.” The cities of New Haven and Bridgeport could be potential hubs for local crowdfunding activity, he said.

But Sayles disagreed with that vision. “This type of crowdfunding is most prevalent in major markets where there are strong fundamentals and investors with a combination of affluence, tech savvy and asset familiarity,” he said. “This would include markets like Boston, Greater New York, Washington, D.C., Seattle, San Francisco and Los Angeles.”

The Westchester County and Fairfield County markets have yet to see a groundswell of crowdfunding projects.

“You would be hard-pressed to find large multifamily deals in these areas,” said Adam Kaufman, managing director of ArborCrowd, a New York City-based crowdfunding platform. “That is a tough market for commercial real estate development. Otherwise we”™d be looking there ourselves.”

In Fairfield County, one of the few real estate investment campaigns to be actively publicized was a 2015 project by New York City-based iFunding, a real estate crowdfunding platform. Crowdfunding was used repay a portion of a $55 million construction loan covering three assets in Stamford ”“ Courtyard Marriott, One Atlantic Street and Residence Inn.

“We did not crowdfund the full $55 million, only $1 million,” said Daniel Drew, vice president and head of real estate at iFunding. “The mezzanine lender”™s use of crowdfunding ”“ $1 million of the $3 million total mezzanine loan ”“ allowed them to strategically manage geographic, asset class and/or sponsorship exposure.”

The iFunding effort in Stamford attracted 47 individual and institutional investors, with financial input ranging from $10,000 to $150,000 per investor. Drew noted that the lack of other high-profile crowdfunding projects for this market can be traced to the distinctive nature of the area”™s commercial property environment.

“Crowdfunding offerings backed by commercial real estate are typically better suited for investment amounts from $1 million to $5 million,” he explained. “Sponsors most attracted to crowdfunding are pursuing investment amounts around this size with relatively shorter investment horizons ”“ one to five years. Submarkets, like Stamford, that have a large inventory of institutional quality assets ”“ offices and hotels ”“ that command low cap rates and large transaction sizes are sometimes not best suited for the current crowdfunding environment. This will likely change as the crowdfunding market evolves to more efficiently compete on larger and lower-yielding opportunities.”

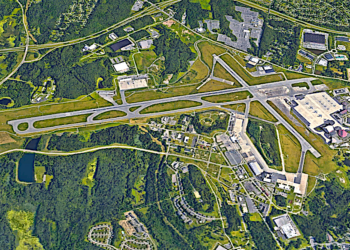

Further east on I-95, EquityMultiple is involved in an ongoing crowdfunding project to raise $1 million to fund the renovation of a multifamily property in Groton within walking distance of the Pfizer campus and Electric Boat. “We see this as an attractive workforce housing asset,” said Clinton. “And we really like that market ”“ there is a strong employee demand, and the naval base and Electric Boat are not going anywhere.”

At RealtyShares, the company has coordinated several commercial property crowdfunding projects in upstate New York, but commercial development opportunities in Westchester and Fairfield counties have so far proved elusive. “It’s a market we are considering and would like to operate in, but the right projects haven’t been presented yet,” Esquivel said.

At HFF, Sayles said he thinks the crowdfunding vehicle will eventually find investors eager to invest in this region.

“There are a whole number of factors, but primarily it is the global search for yield,” he said, “Given the relatively low interest rate environment ”“ negative in some countries ”“ investors are seeking ways to achieve income through their investments.”