It took only hours for Dr. Erik Larsen, assistant director of emergency medical services and emergency preparedness at White Plains Hospital, to hop on a plane for Puerto Rico once he learned his services and expertise were needed by the hurricane-ravaged island.

“The devastation was just everywhere,” said Larsen, who landed in Puerto Rico less than a month after Hurricane Maria laid waste to the region. “It”™s a wreck.”

Larsen was part of a team deployed by the federal National Disaster Medical System, an arm of the Department of Health and Human Services that supplements health and medical systems and response capabilities during times of crisis.

In Puerto Rico, Larsen”™s team operated a medical shelter in Manati, a city about 30 miles west of San Juan. The makeshift medical center was converted from a large sports arena that had been largely undamaged by the hurricane.

“Some of what we were doing was basically being their family doctor, and some of what we were doing was acting like an emergency department,” said Larsen, who serves as chief medical officer of the National Disaster Medical System”™s Region 2, which covers New York, New Jersey, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

The repurposed medical facility in Manati hosted between 40 to 50 chronic patients on the main floor of the arena, many of whom needed ongoing care that could not be provided in homes but was not critical enough to necessitate stays in crowded hospitals. The 24-hour facility also saw hundreds of outpatients daily.

“Sometimes there were long waits when people would come in, and they were so patient,” Larsen said. “You never heard anyone complain about not being seen. They appreciate everything we were able to help them with, and that does make your job very rewarding.”

Though it”™s been more than a month since the hurricane ravaged the area, food, electricity and clean drinking water remain large problems for much of Puerto Rico. Contaminated water has led to a number of health complications for residents, including the potentially life-threatening bacterial infection leptospirosis.

“It really comes down to a lot of the basics,” Larsen said of the region”™s needs.

Despite “the usual problems” of rodents, mosquitoes, habitually failing generators and diets of ready-to-eat meals, his team considered themselves fortunate compared with others on the island, he said. They enjoyed an occasional cold shower and toilets that could be flushed with buckets of water. The sports arena provided a solid roof over their heads, while also serving as a protectant against the onslaught of mosquitos that have overtaken the region.

Aiding in the relief effort in Puerto Rico was not Larsen”™s first foray into disaster response. In fact, it wasn”™t even the first call for help after a natural catastrophe that he”™d answered that month.

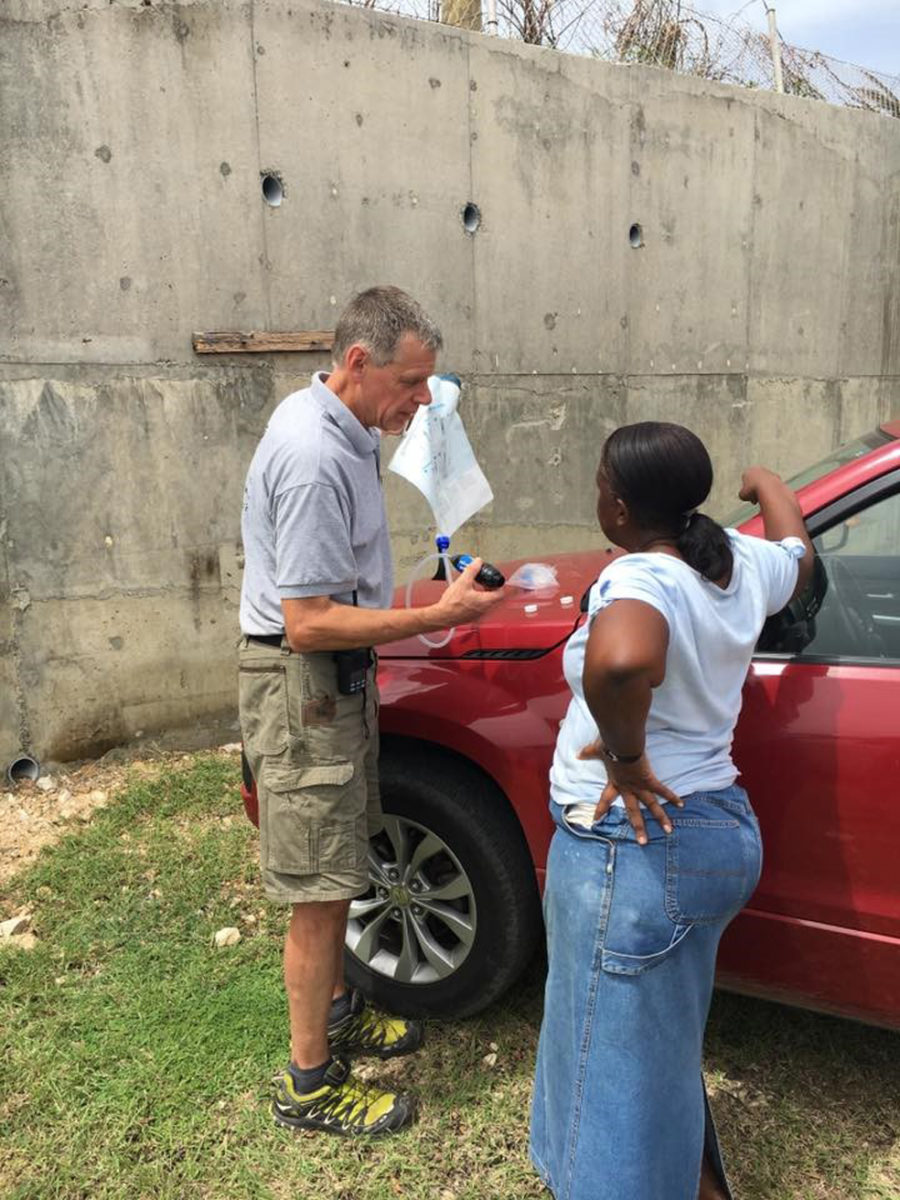

Larsen had been home in New York for only 10 days when he received the call that he was being sent to Puerto Rico. Prior to that, he”™d boarded a private plane with the president of the International Humanitarian Aid Foundation, Andrew Topp, to deliver 500 pounds of medical supplies to the British Virgin Islands, which were devastated by Hurricanes Maria and Irma. Larsen and Topp spent their time on the islands supplying clinics with medicines, emergency medical care equipment and water filtering devices.

Returning home from his trip to the Virgin Islands, “In some ways, I was ready to go sort of back immediately in the field,” the emergency doctor said.

Larsen has always felt drawn to emergency medicine, which led him to pursue the specialty at the Medical College of Ohio. He joined the National Disaster Medical System in 1989, an organization that has put him on the front lines of some of the world”™s most destructive natural disasters, from the 2005 earthquake in Kashmir to the 2010 earthquake in Haiti.

Following Hurricane Katrina, Larsen served as a medical director at the New Orleans International Airport, where he organized the care and transport of the injured, sick and dying and arranged to evacuate 40,000 patients. “That was probably the biggest, most comprehensive operation that I”™ve been involved in or in leadership of,” he said.

Along with natural disasters, Larsen also lends his expertise to pre-planned events through the National Disaster Medical System. He served as chief medical officer at President Barack Obama’s 2013 inauguration, the 2013 Super Bowl and the 2013 and 2014 opening sessions of the U.N. General Assembly.

“When there”™s three quarters of a million people in any place, you”™re going to have people get sick, and a certain number of people will have injuries,” he said. “Hopefully minor injuries, but there will certainly be injuries.”

For Larsen, facing new catastrophes has not become any easier over his nearly three-decade-long career. “Every time, it brings some of it back up. It brings the sadness,” he said. “The best thing actually for me is doing what I”™m doing right now, which is telling people” what he has witnessed in the field. “That”™s been the most therapeutic thing.”

“It is kind of a shock when you come back,” he said. “We were totally involved in this (situation in Puerto Rico) and in a lot of ways, completely cut off from the world. When you come back and you see things sort of operating normally, you”™re kind of like, ”˜Everyone is just sort of going about their business like nothing else is happening,”™ yet we were so involved in this disaster world in which people”™s lives were totally turned upside down.”

At the end of his stint in Puerto Rico, Larsen said he was asked to stay on for an additional two weeks on the island, an opportunity he ultimately declined.

“I need a little bit of a break, mostly just for the responsibilities I have back here,” he said, noting his positions as medical director for multiple ambulatory care agencies in Westchester County and as medical director for the Hudson Valley Regional Emergency Medical Advisory Committee.

To make the trip to Puerto Rico, Larsen had to ask for assistance from his colleagues at White Plains Hospital.

“I had to dump a number of shifts on my fellow ER doctors,” he said. “They”™ve been very good about it. They feel like it”™s their contribution.”

He also plans to take some time for himself after a strenuous few weeks. “My thing is, I recuperate by spending time outdoors in woods, in wilderness, so I will go do some of that just to unwind,” he said.

And then?

“If they asked me to go back (to Puerto Rico) in a different type of leadership role or whatever role, really” he said, “I would, certainly.”