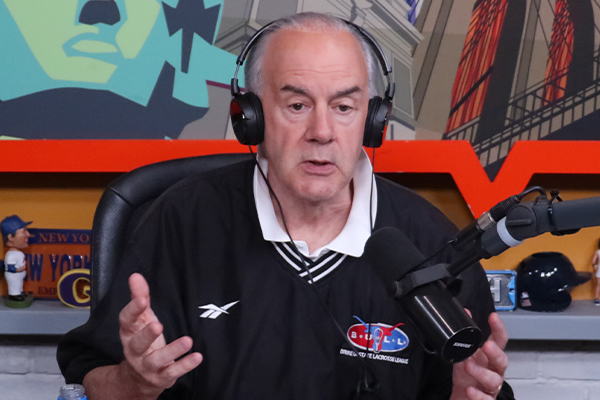

Armonk-based sports psychologist Rick Wolff ”” host of the weekly “Rick Wolff”™s Sports Edge” on WFAN ”” went Kevin Costner one better.

Like Costner”™s Crash Davis in the rowdy 1988 baseball film “Bull Durham,” Wolff was a sharp, talented minor league infielder. Only Wolff was even smarter than Crash. After all, he graduated from Harvard University, where he studied psychology. And though neither ever made it as a player to “the Show” ”” as the major leagues have been called ”” Crash only wonders if he could coach in the big leagues at the end of the movie. Whereas Wolff actually did make it to the Show ”” as the first roving sports psychology coach for the Cleveland Indians (now Guardians) ”” from 1989 to ”™94.

“The 1994 season ended abruptly in August that year due to a players’ strike,” he recalls. “After that season I left the Indians. But the following year, Cleveland won the American League pennant, and the front office awarded me an American League Championship ring, fully engraved with my name, in deep appreciation of my efforts with the players and coaches over the previous five years. (Most of the top players on that 1995 championship team I had worked with extensively during their time in the Indians’ minor leagues.)”

So when it comes to discussing sports performance and mental health ”” an issue increasingly in the national spotlight ”” Wolff has the bases covered, so to speak.

“The field of sports psychology is a relatively new one,” says Wolff, who grew up in the Edgemont section of Greenburgh ”” the son of National Baseball Hall of Fame and Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame sportscaster Bob Wolff ”” and attended Edgemont High School, where he starred in baseball and football. “When I was in college in the 1970s, I had hopes and dreams to be a professional ballplayer. I was lucky to be drafted by the Detroit Tigers,” he adds of playing second base for its minor-league organization in 1974 and ”™75 before realizing his big-league playing dreams would never materialize.

Back then, he says, “not only did teams not have sports psychologists, but it was looked down upon.” Indeed, books like “Fear Strikes Out: The Jim Piersall Story,” a memoir of the Boston Red Sox outfielder”™s emotional struggles that was made into a 1957 movie, stand out partly because they were so unusual at that time. Indeed, it wasn”™t until Wolff had been an assistant baseball coach at Pace University in Pleasantville in 1977 and then head baseball coach at Mercy College in Dobbs Ferry from 1978 to ”™85, that Harvey A. Dorfman, a pioneer in the field of sports psychology coaching with the Oakland Athletics, scouted him for the majors. “I was thrilled and excited to get the call,” Wolff says of their conversation in 1989. Within a few days, six different teams were courting him. He went with the Guardians.

By then, Wolff had a master”™s degree in psychology from Long Island University; a wife, Trish Wolff, who taught English at the Robert E. Bell School in Chappaqua; and three children with whom he played sports. It was perhaps inevitable that “Sports Illustrated” should approach him to write a series of articles about sports parenting, a subject that he has also addressed in numerous books as well as on his WFAN program.

Today, sports psychologists are part of the team landscape as the world becomes increasingly aware of mental health challenges, particularly for young people in the age of Covid. These have been underscored by some high-profile competition withdrawals (Japanese tennis player Naomi Osaka, U.S. gymnast Simone Biles), meltdowns (Russian figure skaters Alexandra Trusova and Kamila Valieva) and controversies (trans swimmer Lia Thomas competing on the University of Pennsylvania”™s women”™s team).

Wolff says that there are two main reasons for the psychological pressures young athletes face. The first is financial as parents see the possibility of athletic scholarships to cover the cost of higher education. But Wolff notes that according to the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), less than 4% of high school varsity athletes are good enough to make their colleges”™ teams.

The other pressure stems from parental and societal expectations as parents and even fans see the young athlete as an extension of themselves and perhaps their own frustrated ambitions for success on and off the field. This frustration manifests itself as early as Little League, Wolff adds, with parents”™ desire to see their children play and excel spilling over into verbal abuse and even violence. It”™s not surprising then that he only works with collegiate and professional athletes, including players from the National Football League and the National Hockey League as well as Major League Baseball, who are mature enough to make their own choices and set realistic goals.

One goal Wolff has set for himself is to help the Save the Game movement, joining its advisory board. Founded by two former Westchester County college baseball standouts ”” Kevin Gallagher”¯(Pace University) and”¯Pat”¯Geoghegan”¯(Mercy College) ”” and former Boston Red Sox infielder Jeff Frye, Save the Game aspires to reverse baseball”™s declining viewership and youth participation. According to its website, there has been a 26.1% decline in playing the game among children ages 6 through 12 since 2008. Meanwhile, World Series attendance has declined from 36.3 million in 1986 to 9.78 million in 2020.

Too much emphasis on hitting home runs and not enough on contact hitting, Wolff says, punctuated by many commercials, is slowing the game and making it boring. Save the Game aims to collect one million signatures on a digital petition to make everyone from MLB officials to parents aware of inspiring a new generation to savor what was once our national pastime through participation and attendance.

Says Wolff: “I believe in the movement and what it”™s doing.”

Catch “Rick Wolff”™s Sports Edge” from 8 to 9 a.m. Sundays on WFAN. For more, visit askcoachwolff.com and savethegameus.com.

If you are experiencing issues with mental health, call the new national hotline at 988.