State workers made $234.3 million in overtime for fiscal year 2019, a $6.1 million (2.7%) increase over 2018, according to the Connecticut Office of Fiscal Analysis.

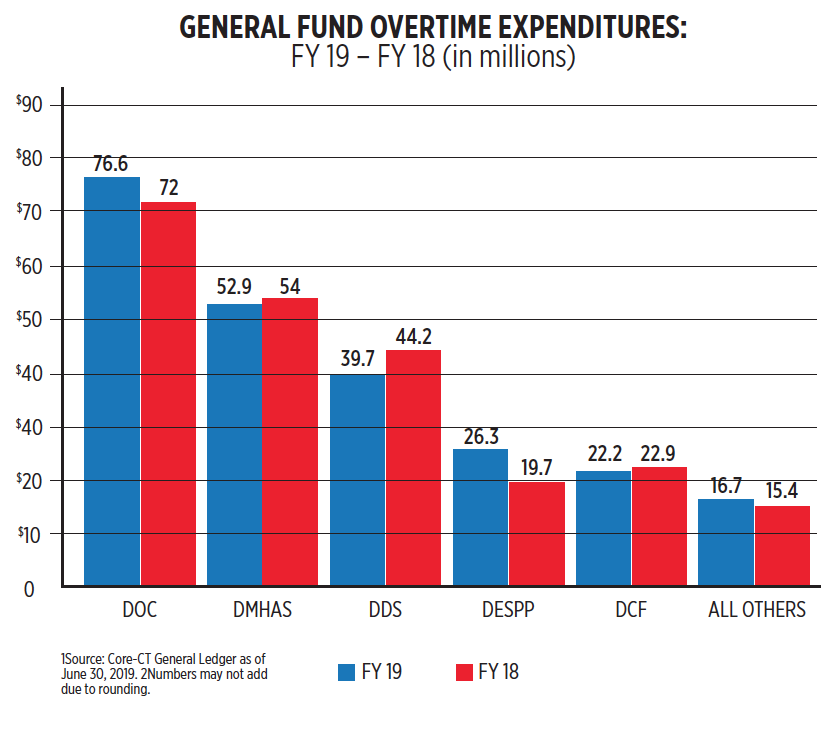

According to its report, five agencies accounted for over 93% of General Fund overtime expenditures in both FY 2018 and 2019: the departments of Correction; Mental Health & Addiction Services; Developmental Services; Emergency Services & Public Protection; and Children & Families.

The largest year-over-year increase was at Emergency Services & Public Protection, whose total overtime rose by $6.5 million ”” 33.1% ”” to nearly $26.3 million.

Registering overtime decreases in fiscal 2019 were the departments of Mental Health & Addiction Services, Development Services, and Children & Families, which collectively reduced overtime by $6.3 million from fiscal 2018. The largest dip was at Developmental Services, which saw overtime decrease 10.3%, or $4.5 million.

Overall, an additional 979 state employees were paid overtime, with 18,333 workers each paid an average $12,780, in fiscal 2019.

The $234.3 million is the third-highest overtime payout in state history. Spending peaked at $256.1 million in 2015, then fell to $219 million in 2016 and $204.4 million in 2017.

The new spike, according to the Connecticut Business & Industry Association, epitomizes what”™s wrong with the state of Connecticut”™s fiscal health ”” and perpetuates the image that this is not necessarily a place where you want to conduct business.

“Businesses that want to come to Connecticut, or are already here and thinking of expanding, see that we”™re one of the most underfunded states in the country,” CBIA Counsel Louise DiCocco said. “Overtime just adds to our long-term liabilities. It”™s a huge, huge problem.”

Overtime is included as a factor in calculating state employee pensions, one of Connecticut”™s most pressing long-term liabilities. While the $234.3 million is less than the $240 million the CBIA warned about in January, DiCocco noted that the difference is barely significant in the big picture.

Overtime is included as a factor in calculating state employee pensions, one of Connecticut”™s most pressing long-term liabilities. While the $234.3 million is less than the $240 million the CBIA warned about in January, DiCocco noted that the difference is barely significant in the big picture.

In March, the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) released its annual study on state pension systems throughout the country. It reported that Connecticut”™s unfunded pension liability amounts to $32,805 per person in the state and 45.13 percent of Connecticut”™s gross state product.

Furthermore, ALEC concluded that the state has only 20.28% of the funds necessary to meet its future obligations to state employees and teachers.

In 2017, then-Gov. Dannel Malloy and the State Employee Retirement Board System (SERS) agreed to lower the assumed rate of return from 8% to 6.9%, increasing the unfunded ratio. The annual cost of SERS is expected to grow from $1.8 billion this year to $2.2 billion by 2022.

The Teachers Retirement System (TRS) maintains an 8% rate of return. Of the latter, the Center for Retirement Studies at Boston College warned that failure to meet that rate could drive the cost of those pensions to $6 billion per year by 2032.

DiCocco noted that Connecticut”™s pension fund liabilities hit $34.2 billion in 2018, against assets of just $13 billion ”” a funding ratio of just 38%, one of the worst of any state.

In June 2011, the pension fund had $10.1 billion in assets and $21.1 billion in liabilities; by June 2018 the fund”™s liabilities had grown by $13.7 billion while assets grew just $2.9 billion, leaving a shortfall of $21.2 billion. Connecticut was meeting just 48% of its obligations in June 2011, and that ratio has continued to decline ever since.

DiCocco applauded the July announcement of a new agreement between the state and the State Employees Bargaining Agent Coalition, which according to Gov. Ned Lamont will result in a budgetary savings in the general fund for each fiscal year through 2032 of between $115 million and $121 million. It will also create a savings in the special transportation fund of $15.7 million in FY2020 and $19.7 million in FY2021.

Nevertheless, she said, something must be done about the overtime conundrum ”” namely, reducing the size of government, making it more efficient and possibly privatizing some state services, all of which Lamont and some state legislators have publicly considered.

“The calculation of overtime is the big stickler,” DiCocco said. “A lot of legislators probably won”™t speak out about that for various reasons ”” some obvious, some not so obvious.”