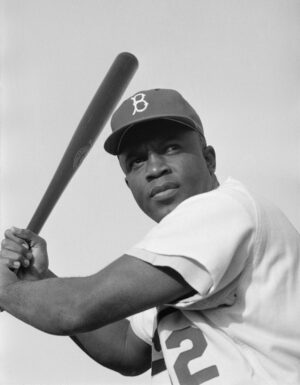

(Editor’s note: The word “legend” is often overused but is probably too little to describe Jackie Robinson, who broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier in 1947 – starring at second base for the Brooklyn Dodgers and enduring horrific abuse in the process, which he bore with grace. His steady presence and sparkling play opened the door for other gifted Black players and later other minorities. His Dodgers career (1947-56) also marked the beginning of many firsts – first Black television analyst in MLB and the first Black vice president of a major American corporation, Chock full o’Nuts. In the 1960s, he helped establish the African American-owned Freedom National Bank in Harlem.

For his achievements, Robinson (1919-72) would be posthumously awarded the Congressional Gold Medal and the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the United States’ highest civilian honors. Not surprisingly, the Robinson family had difficulty finding a home in the mainly white enclaves of Westchester and Fairfield counties. They were ultimately able to build their dream home at 95 Cascade Road in North Stamford with the help of Richard L. Simon, co-founder of the publishing house Simon and Schuster, and his wife, Andrea Heinemann Simon, a civil rights activist.

The couple, who owned the Newfield Avenue estate on which the Mead School now sits are probably better-known today for their talented offspring – opera mezzo-soprano-turned-Realtor Joanna Simon; singer-theater composer Lucy, photographer Peter and singer-songwriter Carly, the first artist to win an Oscar, a Grammy and a Golden Globe for writing and performing a song for a film – “Let the River Run” from “Working Girl,” 1988. Though she grew up wanting to play centerfield for the New York Yankees, Carly would become the unofficial mascot of the rival Dodgers, courtesy of Robinson, who tried to teach her to hit left-handed.

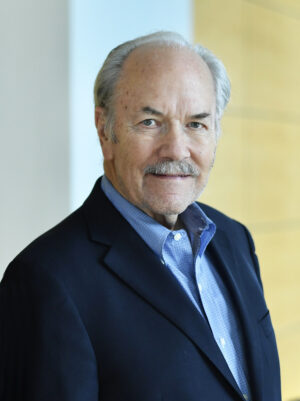

Here John R. Nolon, distinguished professor of law emeritus at the Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace University in White Plains, remembers Robinson and community organizer Roy Echols’ key efforts in establishing lower-income housing in Yonkers: )

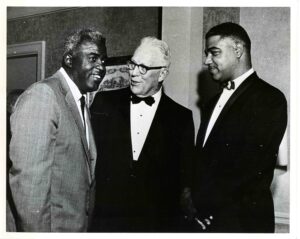

Watching Major League Baseball celebrate Jackie Robinson Day on April 15 reminded me of when I once met him along with Roy Echols, a community organizer in Yonkers.

When I returned from serving in the Peace Corps in Guatemala in 1969, I had been accepted as a Reginald Heber Smith Community Law Fellow to work in an Office of Economic Opportunity- funded legal services program. I was randomly assigned to work in Yonkers, providing legal assistance to the Community Action Program and its staff. During my first week there, Echols, a determined CAP staffer, came into my office, slapped his large fist on my small desk, cursed the lack of affordable shelter and told me we were going to build affordable housing and that I needed to figure out how to do it.

We formed a nonprofit called the Yonkers Community Improvement Corporation (YCIC) and rented a storefront on Warburton Avenue. I boned up on housing development and finance, we found a deteriorated park in the Hollows neighborhood, got it released by the New York Legislature from the state’s public trust requirements and found a developer-cosponsor to build two 12-story buildings with 195 low-income housing units on that parcel.

We spoke to Whitney M. Young Jr.’s widow, Margaret Buckner Young, and got her permission to use the name of her late husband – a New Rochelle-based civil rights leader who was influential in the federal government’s War on Poverty in the 1960s – for the project. She asked that we interview Robinson, who by then was long retired from baseball and had a construction company. Our storefront was small, and the Warburton Avenue neighborhood was littered, poorly lit and frankly scary at night. But it was there early one evening in 1971 that we met with Jackie, Rachel, a nurse who become the director of nursing at the Connecticut Mental Health Center in New Haven, and a construction manager and agreed to a term sheet for a contract to construct Whitney Young Manor. It provided shelter to lower-income families for more than 30 years; was purchased by a new developer, Omni New York, in 2006; underwent an $11 million restoration; and continues to be rented to low-income households. Today a 1,320-square-foot apartment for a family of four with income under $77,000 rents for around $2,000 a month. I’d estimate that more than 600 individuals have obtained shelter in the manor for nearly 50 years. That’s 10,950,000 individual nights of shelter.

Having learned about affordable housing development, I was hired by Yonkers as deputy corporation counsel and the deputy director of the Department of Planning and Development to help develop more housing. In 1974, I was recruited to set up and run the Housing Action Council, which is still working today, building and rehabilitating lower-income housing. I’d estimate that the Housing Council’s work has resulted in 15,000 units of low and moderate housing in the nearly 50 years it has existed, providing shelter for another 45,000 individuals.

Robinson’s contributions are well known and widely respected. Echol’s hand slap on my desk and the contagious energy of his determination, not so much. It was a small chance event that resulted in significant change, providing shelter for so many and teaching that our individual actions can count.

John R. Nolon is distinguished professor of law emeritus at the Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace University where he supervises student research and publications regarding land use, sustainable development, climate change, housing insecurity, racial inequity and the coronavirus pandemic. He is co-counsel to the law school’s Land Use Law Center, which he founded in 1993. He served as adjunct professor of land use law and policy at the Yale School of the Environment from 2001 to ’16. Before he joined the law school faculty, he founded and directed the Housing Action Counsel to foster the development of affordable housing.