by Hugh Bailey

Hearst Media Connectcut

The commute in southwestern Connecticut is a costly one.

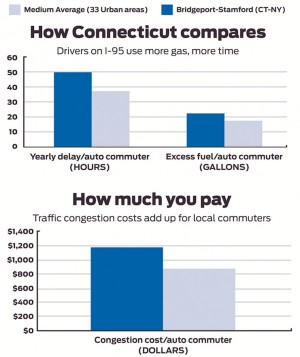

Data from Fitch Ratings shows that drivers in the Bridgeport-Stamford metropolitan area spend a greater amount of time in their cars and use more gas, which leads to more money wasted than other regions of similar size. Mass transit helps, but not enough to change the equation.

Commuters here spend an average of 49 extra hours in traffic in this region annually, compared with 37 hours in similar-sized areas, according to Fitch.

“The Bridgeport area is way above the median,” said Jamie Goh, an analyst with Fitch”™s Global Infrastructure Group. “The cost per commuter is $1,174 annually. If you quantify it, that”™s second among all medium-sized urban areas.”

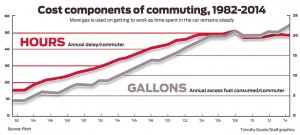

And despite some movement away from driving to work, the costs and amount of gas used have been trending higher for more than 30 years.

And despite some movement away from driving to work, the costs and amount of gas used have been trending higher for more than 30 years.

“The trend has been increasing since 1982,” Goh said, adding that the region is second only to Honolulu in terms of congestion.

The state of Connecticut has taken steps to tackle the issue, with the Let”™s Go CT plan that includes a five-year and a 30-year plan to bring the state up to speed and build an infrastructure more in line with a modern economy. But high costs and uncertain funding could complicate matters.

“It”™s an acknowledgment by the state government of the chronic level of underfunding,” said Saavan Gatfield, a senior director in Fitch”™s Global Infrastructure Group. “There”™s clearly a capacity issue in the area.”

Rising stress

The travel-time index is a measure of how long a trip takes at peak times compared with regular conditions, and the data since 1982 shows a slow, steady increase, with a flattening since the recession. What used to be a roughly 1.2 rating ”” meaning a 10-minute trip in normal circumstances would take 12 minutes at peak periods ”” has inched up to about 1.4.

That adds minutes to drive times and can send stress levels soaring, as well as cutting into economic activity. And the Bridgeport-Stamford region is right near the top of the list of comparable-sized regions.

At the same time, vehicle-miles traveled has shown a decline on a per-capita basis. “VMT generally has been down nationally since 2007, and you see that reflected in Connecticut, as well,” Gatfield said.

But while the decline might slow some of the growth in congestion, it hasn”™t affected the overall problem.

“Even though the economy is growing as a whole, the lines indicate a flattening trend,” Gatfield said. “Metro-North ridership has been increasing in that time. ”¦ The effect is to alleviate growth in congestion, but not congestion itself.”

Commuter train travel only affects one portion of highway traffic, he said.

“It clearly helps take some of those long-distance journeys off the road. Improvements to transit will continue to do that,” he said. “But you still have local traffic as commuters still need to get to the station. And not all traffic is making longer-distance commutes to places that are connected by Metro-North.”

Mass transit is one part of a wider solution, Gatfield said.

“Of course it will have an effect, but it”™s not the whole solution,” he said.

Increased capacity

Among the many facets of the state”™s long-range transit improvement plan is widening interstates, including I-95 from Bridgeport west. Work has already begun widening I-84 in the Waterbury area.

Among the many facets of the state”™s long-range transit improvement plan is widening interstates, including I-95 from Bridgeport west. Work has already begun widening I-84 in the Waterbury area.

But experts have warned that in many cases adding highway capacity simply attracts more drivers, as people who might have stayed off the roads are attracted by the extra lanes and the promise of more efficient travel.

The effect in many cases has been that adding highway capacity has little impact on congestion. But the scope of the problem in Fairfield County makes more lanes a necessity, analysts said.

“Clearly we can see capacity is needed,” Gatfield said. “It would help in solving part of the problem that has already built up at key interchanges.”

In addition to the $5.7 billion widening of I-95 in southwestern Connecticut is a two-phase $800 million project for I-84 from the New York line to Exit 8 in Danbury, as well as a $500 million program linking I-95 to the Merritt Parkway in Norwalk along a new Route 7.

Finding the money

Gov. Dannel P. Malloy last week said a committee looking for ways to finance his proposed 30-year, $100 billion transportation overhaul can take more time, adding that he wants state lawmakers to put a question on the November 2016 ballot to prevent transportation funds from being spent on other matters. A constitutional amendment would be required.

No matter the outcome, paying for the planned improvements is a major sticking point. While federal funds once accounted for a great majority of highway spending, the mix with state funds has moved close to a 50-50 split in recent years, analysts said.

The federal gas tax is less reliable because of the rise of fuel-efficient vehicles, Gatfield said, an issue that will be exacerbated by rising efficiency standards.

Highway tolls, which have been off Connecticut highways for decades but are under discussion for a return, could raise money while also affecting when people choose to drive. But they are far from a sure bet.

“It”™s difficult to know what the outcome in Washington will be,” Gatfield said. “You can see various states taking initiative to various degrees, in the form of higher taxes, increased use of public-private partnerships or other sources of capital to make infrastructure improvements that are necessary.”

Hearst Connecticut Media includes four daily newspapers: Connecticut Post, Greenwich Time, The Advocate (Stamford) and The News-Times (Danbury). See ctpost.com for more from this reporter.