The chairman and chief executive of the country”™s biggest bank sidestepped questions from Congress earlier this week about the events that led to more than $2 billion in losses for a London-based trading unit of JPMorgan Chase & Co.

Jamie Dimon told the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs that traders belonging to the bank”™s Chief Investment Office “did not have the requisite understanding of the risks they took” as they strove to reduce the unit”™s synthetic credit portfolio in advance of new Basel capital requirements.

Dimon said CIO”™s strategy for reducing its synthetic credit portfolio ”“ which was originally intended to protect, or hedge, the bank against a systemic event such as the European debt crisis ”“ was “poorly conceived and vetted.”

“The strategy was not carefully analyzed or subjected to rigorous stress testing within CIO and was not reviewed outside CIO,” Dimon said in prepared statements.

However, when questioned by senators over the distinction between hedging and engaging in proprietary trading, and whether JPMorgan”™s traders crossed from the former to the latter, Dimon did not answer directly, expressing his belief that the CIO trades were engineered to protect the firm but adding that it is not always possible to distinguish between hedging and proprietary trading.

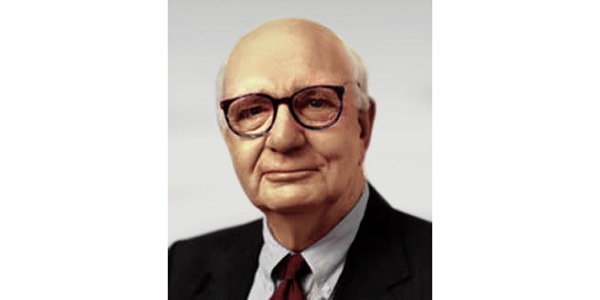

During a recent speach at Columbia Law School, Paul A. Volcker, former chairman of the Federal Reserve and of President Obama”™s Economic Recovery Advisory Board, raised the question of whether JPMorgan was using the CIO as a means of engaging in proprietary trading.

“Were they in fact using this unit that they had as a kind of speculative trading vehicle? Were they in fact trading in derivatives in a way that was not a protection against loss but a proprietary guess as to which way the market is going to go?” Volcker said.

He left his questions unanswered, but said the distinction between hedging and proprietary trading ”“ a practice by which investment banks conduct trades for their own profit rather than on the behalf of their clients ”“ “is the area outside of the ordinary trading desk that probably presents the biggest challenge.”

Volcker gave the keynote speech at a June 7 symposium on competition and consumer protection in the financial services sector. The event, co-sponsored by Columbia Law School and the American Bar Association Section of Antitrust Law, featured representatives from the Federal Trade Commission, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and the New York Federal Reserve Bank, among others.

The previous day, Federal Reserve Governor Daniel Tarullo told the Senate Banking Committee that if the Volcker Rule, which prohibits proprietary trading by U.S. banks, had been in place sooner, regulators might have known earlier of JPMorgan”™s hedging strategy.

“If a firm said, ”˜We are doing this as a hedge,”™ they would be required to explain to themselves internally as well as to the primary supervisor, what the hedging strategy was … and how they would make sure it didn”™t give rise to new exposures,” Tarullo told the Senate Banking Committee, according to Reuters.

While the Volcker Rule has yet to be implemented by Congress, banks have largely already abandoned what they admit is pure proprietary trading, Volcker said.

However, he predicted banking regulators would continue to struggle as they seek to protect consumers and guard against the types of risky investments that contributed to the economic downturn.

While the phrase “too big to fail” is frequently cited, Volcker said the real distinction should be “too big to manage.”

“Maybe this JPMorgan thing is an illustration that these things are really hard to manage,” Volcker said. He added that seeking to effectively regulate some of the country”™s biggest banks “can be difficulty squared.”

Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) echoed Volcker”™s concerns, saying at the Senate hearing on JPMorgan”™s trading activities that “executives and regulators simply can”™t understand what”™s happening” in many of the larger banking institutions.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau was created by Dodd-Frank as a means of attempting to centralize those government agencies that regulate the financial industry.

In creating the CFPB, Congress did not fully accomplish that goal, though, said William E. Kovacic, former chairman of the Federal Trade Commission and one of the speakers at the June 7 symposium.

“One of the most important issues today among competition and consumer protection bodies globally is the identification of the right regulatory design,” Kovacic said. “Dodd-Frank doesn”™t solve that ”“ it only went partway ”¦ It doesn”™t go all the way in achieving unification of responsibility and everything that might come from that.”