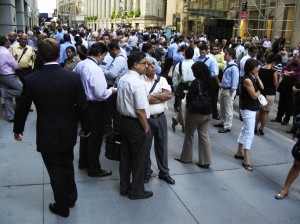

As rattled Manhattan workers streamed out of office towers following the afternoon earthquake Aug. 23, many hit the road home for Fairfield County rather than return to their desks.

It came as a symbolic contrast of sorts to the earthshaking cataclysm of 9/11, when Manhattan companies chose to return “home” to the city rather than embark on a permanent exodus to the suburbs.

Observers expected that steady stream north to Fairfield County and Westchester County, N.Y., which coupled abundant class-A office space with a familiarity for many executives who commute daily to the city.

As Tropical Storm Irene proved, the suburbs are also susceptible to emergencies causing widespread business disruptions but obviously do not face the challenges of New York City.

“I think there was a real concern that the whole World Trade Center area would become a wasteland,” said Laure Aubuchon, Stamford”™s economic development chief who previously worked in the office of New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, leading international development. “There was 10 million square feet of office space that went down that day. Put that in perspective: Stamford has 13 million square feet. People forget that there was damage all around ”“ there were a lot of buildings that were uninhabitable.”

For companies that did take the opportunity to set up satellite offices, Jersey City, N.J., proved the biggest draw, Aubuchon added, due to its proximity across the Hudson River and the fact that it had a large amount of available space at the time.

“About a week later there was much discussion about the large amount of commercial office space that was lost in the city,” recalled Jack Condlin, president of the Stamford Chamber of Commerce. “The question was, ”˜Is there sufficient space in Manhattan to absorb the displaced businesses?”™ The chambers in Fairfield County quickly put together a list of available spaces that could be occupied. Several businesses did take advantage of some of this space.”

In a September 2002 study, New York City”™s comptroller determined that 84 percent of the companies dislocated from Ground Zero found alternate quarters in New York City, while more than 10 percent chose New Jersey. Cantor Fitzgerald, Citigroup and American Express were among those that situated workers in Connecticut, accounting for a small percentage of the overall number of workers finding temporary quarters.

“There was a lot of scuttlebutt, and very little action,” said John Hannigan, principal of Choyce Peterson, a commercial real estate brokerage company in Stamford.

Last spring, reports surfaced that UBS AG was considering the new World Trade Center building under construction as a potential new Manhattan office ”“ rumored at the time to include employees currently in Stamford. More than a few people in Connecticut wondered aloud how workers would feel about commuting each day to a building that could represent a hugely visible target, regardless of the viability of terrorists actually plotting an attack on it.

In one sense, UBS remains the six-degrees-of-separation link to those days ”“ American Express leased nearly 200,000 square feet of space at 400 Atlantic St. in Stamford with the intent of relocating employees there from New York City in the aftermath of 9/11. But the credit card giant would end up subleasing much of the rest of the space to UBS, which used it as an overflow office of sorts to accommodate its rapid expansion in the most recent business cycle.

In Westchester County, Morgan Stanley established a facility in the aftermath of 9/11 but commercial brokers say that deal was as much a function of the good price Morgan Stanley commanded as it was from any plan to distribute job functions geographically. For New York City companies relocating to Fairfield County over the subsequent decade, however, the primary reasons were to alleviate ballooning rents and commute times, rather than employee unease over being packed into a city with 20 million other people who might want to get out.

Fears ebbed even as terrorism incidents continued, first when the mysterious anthrax mailings jangled nerves anew in October 2001 and then with the December 2001 attempt to blow up an airliner by detonating a shoe bomb. New York City received a reminder of its vulnerability last year after the failed attempt by a Pakistani living in Bridgeport to detonate a car bomb at Times Square and by last month”™s earthquake.

Ten years after 9/11, it is Manhattan”™s office market that has led the recovery, despite large blocks of attractive office space in Fairfield County and public officials eager to recruit Big Apple businesses over the border.

“I think with regard to the corporate exodus, it certainly happened on a temporary basis ”“ but ”¦ people came back,” Aubuchon said.