“This we know: The earth does not belong to man. Man belongs to the earth. This we know: All things are connected like the blood which unites one family. All things are connected. Whatever befalls the earth befalls the sons of the earth. Man does not weave the web of life. He is merely a strand in it. Whatever he does to the earth, he does to himself.” – Attributed to Chief Seattle, a leader of the Duwamish and Suquamish peoples, (circa 1780~86 – 1866)

With the incoming Trump Administration planning to streamline climate initiatives and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), green organizations may be finding new urgency in the adage “think globally, act locally.”

“Local conservation has always been an urgent need,” said Kara Hartigan Whelan, president of the Westchester Land Trust, based at Sugar Hill Farm in Bedford Hills.

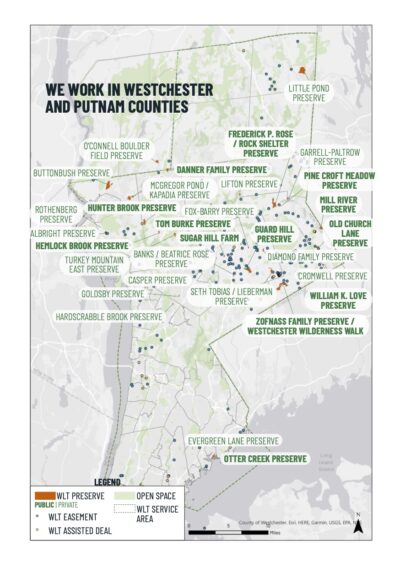

Founded in 1988 by Louis McCagg, a coalition builder in land conservation, urban planning, civil rights and education, with visionaries like former New York Lt. Gov. and Westchester County Executive Alfred B. DelBello, the trust preserves public and private lands in Westchester and Putnam counties in perpetuity through conservation easements and acquisitions, working with municipalities — as in the case of the 383-acre Leon Levy Preserve in Lewisboro, where the town owns the land and the trust holds the easement — and with private landowners to monitor easements on their property that stay with the land as it passes from one owner to another.

In the latter instance, the trust also works with Realtors to help them understand such stewardship, Whelan added. It’s just one way that the trust, with a staff of 12 and a current budget of just under $2 million, partners with the local business community, including appraisers and attorneys, to educate the public and retain open space for its enjoyment and natural habitation.

To date, the accredited trust has protected more than 9,250 acres, including 1,200 that are open to the public. Among the 14 public preserves is the flagship Westchester Wilderness Walk/Zofnass Family Preserve, 127 acres in Pound Ridge, with an arboretum and seven and a half miles of trails.

“It’s really terrific, with lovely woodlands and wetlands,” Whelan said. “People love to explore it for a day.”

The newest of the public preserves is the Mill River Preserve in South Salem, which opened Saturday, Nov. 23, adjacent to The Leon Levy Preserve. “We like to build out,” she added of the connectivity – connecting one open space to another – that is key to the trust. Another example: The trust is restoring the 174-acre Little Pond Preserve in Patterson in Putnam – which contains a rare floating bog, important to biodiversity – with plans to sell it to New York state to become part of its wildlife corridor.

“We’re also trying to give our forests a fighting chance,” Whelan said, referring to threats from pests and pathogens causing beech leaf disease and oak wilt as well as invasive vines like bittersweet and porcelain-berry. Some of these enter our environment through trade, although warmer temperatures that favor some species over others are also a factor. (New York City has been reclassified as one of the northernmost humid subtropical cities — good news for newcomers like Japanese flower apricots, camellias and lofty crepe myrtles but not so great for familiar birches and sugar maples.)

An anonymous $100,000 grant is enabling the trust to cut invasive vines in 60 targeted areas across 13 preserves, plant 450 trees in 11 preserves, protect young trees outside deer exclosures at 10 preserves and erect a 10-acre deer fence at the Frederick P. Rose Preserve in Waccabuc.

But the connectivity Whelan spoke of is not limited to connecting properties. It’s also about connecting people to the land. On Tuesday and Thursday mornings from April to October, Allison Turcan, founder and executive director of D.I.G. (Dealing in Good) Farm in North Salem, works with scores of volunteers – from student athletes to corporate executives – to plant vegetables in a garden at Sugar Hill Farm for food pantries like the Community Center of Northern Westchester in Katonah. Over more than 10 years, the program has yielded close to 80,000 servings of vegetables.

Through the “A Love Letter to Nature” initiative, the trust distributed 450 “grow bags” to Mount Vernon High School in 2023 to enable students produce tomatoes, lettuce, cucumbers, squash and herbs. This year, the trust worked with the Port Chester Middle School and will continue to partner with both schools, Whelan said.

“It’s a great way to relate to the kids and connect them to where food comes from,” Whelan said.

A Chappaqua native, she has always been connected to the land, beginning at Sacred Heart Greenwich, when she “got the bug to build a nature trail.” At 16, she was dogsledding in Minnesota as part of Outward Bound, an international network of outdoor educational organizations. She earned a Bachelor of Science degree in environmental studies from Boston College and a Master of Science degree in environmental policy from the University of Michigan before embarking on a career at land trusts that included eight years at the Greenwich Land Trust.

With the Westchester Land Trust since 2012, Whelan, a South Salem resident, said, “I feel lucky to do this.”

The Westchester Land Trust relies mostly on individual donations as well as grants and family foundations for its support. For more, call President Kara Hartigan Whelan at 914-234-6992, ext. 12.