“Faith, family and football” is a code that many in the NFL have tried to live by, to which Andy Robustelli, star defensive end with the Los Angeles Rams and the New York Football Giants in the 1950s and ’60s and a prominent Stamford entrepreneur, would have added one other word – business.

Indeed, after his football career (1951-64) and even during his tenure as the Giants’ director of operations (1974-79), Robustelli ran two family businesses – National Professional Athletes (NPA), a marketing company that teamed football players with other enterprises; and a William Fugazy travel agency franchise, Robustelli Westheim Travel Co., which became Robustelli World Travel Inc. They in turn became part of Robustelli Corporate Services around 1970. By the time it was sold in 2008, it was grossing $90 million to $100 million a year, netting roughly 2%.

“My father loved business,” said Bob Robustelli, himself the owner of Robustelli Worldwide LLC, an international corporate events company, and the author of “The Pope of the NFL: The Andy Robustelli Story and the Family That Loved Him,” published Aug. 31 on Amazon. The incisive story is edited by Peter Golenbock — perhaps best-known for two absorbing books on the New York Yankees, “Dynasty: The New York Yankees, 1949-1964” and “The Bronx Zoo” – whom Robustelli met through a mutual Stamford friend, former New York Mets Manager Bobby Valentine.

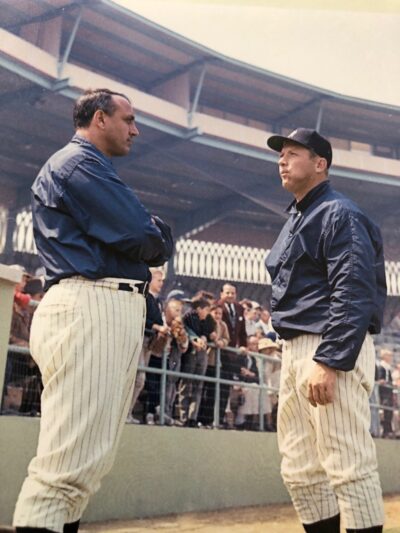

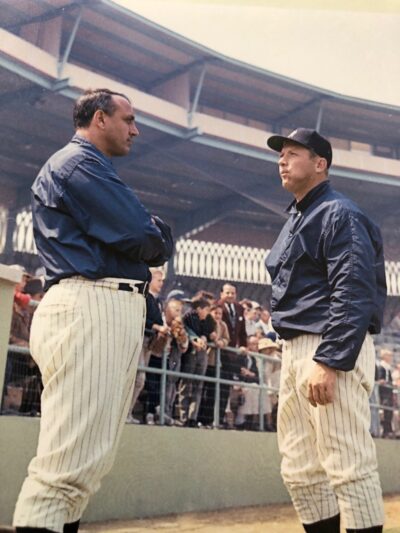

That Robustelli and Golenbock should come together to tell this “pope’s” story – Andy was called that for his propensity to keep his teammates on the straight and narrow, his son said – was perhaps inevitable. Both the Giants and the Yanks once shared a home, Yankee Stadium, and still share a fan base as Giants’ fans tend to root for the Bronx Bombers and New York Knicks, whereas fans of the Mets and New York Jets – teams that once shared Shea Stadium — tend to pair up and also embrace the Brooklyn Nets.

From a business standpoint, the Yankees and the Giants are two of the most successful sports franchises globally. On Forbes’ 2023 list of “The World’s 50 Most Valuable Sports Franchises,” the Yankees are No. 2 at $7.1 billion, behind the Dallas Cowboys ($9 billion). The Giants – celebrating their 100th anniversary in 2025 – are No. 6 ($6.8 billion) behind the Golden State Warriors ($7 billion), the New England Patriots ($7 billion) and the Los Angeles Rams ($6.9). Rounding out the top 10 are the Chicago Bears ($6.3 billion), the Las Vegas Raiders ($6.2 billion) and, tied for ninth at $6.1 billion, the Knicks and the Jets.

Robustelli said he sees two patterns in this. Teams like the Giants and the Yankees come from big-city markets with loyal fan bases. The other is that seven of the teams in the top 10 are football teams. With respect, Robustelli said, baseball is no longer our national pastime. Football is. (Perhaps baseball can console itself with being the more international sport, with many stars coming from Latin America and Japan in particular. Also, baseball’s relationship with the Olympics, which has bounced around like a knuckleball, is on again as it returns in 2028 at the Los Angeles Games.)

However, football was not the powerhouse it is today when Andy was growing up in Stamford in a devout Italian-American Roman Catholic family, attending Mass on Sundays and Stamford public schools – where he played baseball and basketball as well as football in his senior year at Stamford High School – before enlisting in the Navy and heading off to World War II’s Pacific Theater. On his return, he earned a degree in physical education from Arnold College – the first coeducational college for hygiene and physical education, now part of the University of Bridgeport’s College of Education.

Upon graduating, Andy got a job offer in the Nutmeg State that would’ve put him on the path of teaching and coaching. But he was also drafted by the Rams in 1951. Family friend Walter Kennedy, who would become mayor of Stamford and commissioner of the National Basketball Association (NBA), advised Andy to play it safe.

“But his father – my grandfather Lucien – said you’ll never know if you don’t take the chance,” Robustelli said.

A good thing, too, that Andy took the chance as he would play in eight NFL championship games – two with the Rams and six with the Giants, winning a championship with each, including in his first season with the Giants (1956) on a team replete with other Hall of Famers – running back Frank Gifford, offensive tackle Roosevelt “Rosey” Brown, offensive coordinator Vince Lombardi and defensive coordinator Tom Landry. The championship appearances – the Super Bowl was not inaugurated until 1967 – included the Giant’s “painful” loss to the Baltimore Colts in 1958, which would prove pivotal as the first football game televised nationally, Robustelli writes:

“From that day on, football would be the most popular sport of them all.”

Four years later, Andy received the Bert Bell Trophy, the only defensive player ever to win this MVP award. He was named to the All-Pro first team eight times and the All-Pro second time four times. He was selected for the Pro Bowl game seven times.

When his playing career ended in 1964, Andy applied his business acumen to a number of successful ventures that included (with friend Ed Clark) Ed & Andy’s sporting goods store as well as National Professional Athletes and Robustelli World Travel – even using Emery Air Freight to overnight plane tickets to clients at a time when that was unusual. But Andy’s career with the Giants was about to enter a new phase.

Founded in 1925 by Timothy James Mara with a $500 investment, the New York Football Giants –as they have been legally known to distinguish themselves from the then New York Giants baseball team – foundered in the late 1960s and the early 1970s, paralleling the Yankees’ wilderness period. Owners Wellington Mara, the founder’s younger son, and Tim Mara, Wellington’s nephew, did not, in Robustelli’s diplomatic words, “see eye to eye on some issues.” The Maras approached Andy to become the team’s director of operations, which he agreed to do for five years. (Today, the team is owned by Wellington’s son John, who lives in Rye, and Steve Tisch, son of the team’s co-owner from 1991 to 2005, Bob Tisch.)

Robustelli said that his father’s football talent and business experience prepared him to help bring the Giants into the modern, computer era.

“He was very organized. He could do organizational charts forever.” At the same time, Robustelli added, “He was ahead of his time, sometimes too much ahead of his time. He was a hell of a businessman.”

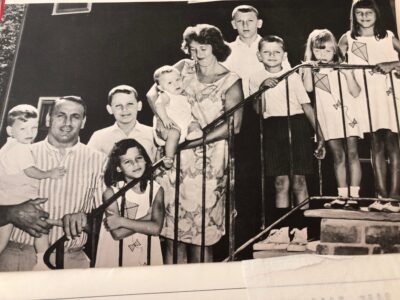

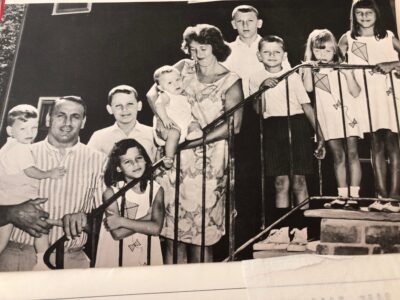

Even while serving as Giants director of operations, Robustelli said, his father would continue to work in the evenings at what had become a family business, with eight of his nine children taking part.

Robustelli doesn’t shy away from what was a challenging relationship, particularly during his teenage years.

“He was tough but fair. He wasn’t home all the time, but you knew his presence was there.”

The author remembered his father as a disciplined, driven man who believed in respect – for God and others, including some 60 to 70 employees. He always called Wellington Mara, with whom he had a special relationship, “Mr. Mara.” When Mara insisted he call him by his first name, Andy responded, “OK, Mr. Mara,” Robustelli said. It was Giants teammate – and fellow Giants Ring of Honor inductee – Dick Lynch, who was the source of the “pope” nickname. As legend has it, Robustelli said, Andy was getting on some carousing teammates, reminding them of their family-men reputations and a big game coming up. Lynch knelt down and kissed Andy’s ring.

The “pope” passed on May 31, 2011 at age 86, two months after the death of wife Jeanne, whom Robustelli writes was the love of Andy’s life. Robustelli, who had worked his way up to sales executive in the family business, continues to set up meetings and events for corporations in his own company, as well as write novels, including the spy novel “Teamwork.” He coached Little League for 35 years and high school sports for six, serving as athletic director for Trinity Catholic High School for four years. He’s still coaching flag football for second and third graders.

“I can’t stop,” he said. “I don’t want to stop.”

Spoken like his father’s son.