When it comes to the so-called new normal in retail, MJP Consulting principal Michael Berne says, there is no such thing.

Berne made those remarks at a recent webinar hosted by the nonprofit Connecticut Main Street Center, which advocates for developing and sustaining successful downtowns that meet the needs of residents and visitors.

Berne, who touts himself as one of North America”™s leading experts and futurists on urban and downtown/Main Street districts, as well as the retail industry, said that despite the “gut punch” that downtown districts and retail in general suffered during the pandemic, not all is as bad as some have opined.

“Retail is the most intricate and fast-moving property type there is,” he declared. “It goes in directions that most people never would have predicted.” Simply extrapolating the future from current trends “is where we run into problems,” he added.

“The reality is that always with retail but especially right now, there is so much we still do not know ”” or that we think or are sure we know, but where we are likely to be wrong,” Berne said.

Acknowledging all the predictions of doom in spring 2020, Berne said that 18 months later, the truth began to emerge that “this was not an extinction-level event for downtown retail ”” far, far from it.”

In contradiction to popular perception, Berne argued that the restaurant sector has not been as damaged as commonly believed. While the independent restaurant coalition had estimated that as many as 85% of those restaurants would close, he said the reality was actually far more positive.

In an average year, Berne said, U.S. restaurants generate an estimated $909 billion in revenue; in the course of 2020, they generated about $669 billion.

“That”™s massive,” Berne said, “but looking at it another way, 90,000 restaurants closed permanently or long term,” according to the National Restaurant Association, which had originally estimated 110,000. In an average year, he said, 50,000 restaurants close.

What the NRA never reported, he said, was that 70,000 restaurants opened in 2020 ”” a figure that was “not bad,” given that 83,000 normally open each year.

“Not good ”” not cataclysmic,” he concluded.

In Connecticut, Berne added, the state”™s restaurant association reported that 600 of 8,500 restaurants had closed permanently or long term ”” a 7% decrease. “That”™s lower than in an average year,” he said. “And in many cities, more restaurants opened than actually closed,” including Stamford.

“That National Restaurant Association was doing a little bit of posturing and negotiating,” Berne continued. “And it worked,” with the passage of the federal Restaurant Revitalization Fund and easing of restrictions surrounding outdoor dining, to-go alcohol sales and the like.

Other small businesses similarly benefited from curbside pickup, as well as from “the massive amount of government assistance,” including the Paycheck Protection Program, stimulus checks, state grants and property owners who were receptive to reduced, deferred or extended leases ”” in turn made possible by the banks.

Some retail categories “did even better than in a normal year,” he continued, citing the home, kitchen, garden, crafts, toys and sporting goods sectors. Berne acknowledged that “it”™s not at all clear” that those sectors will continue to boom as the pandemic wanes.”

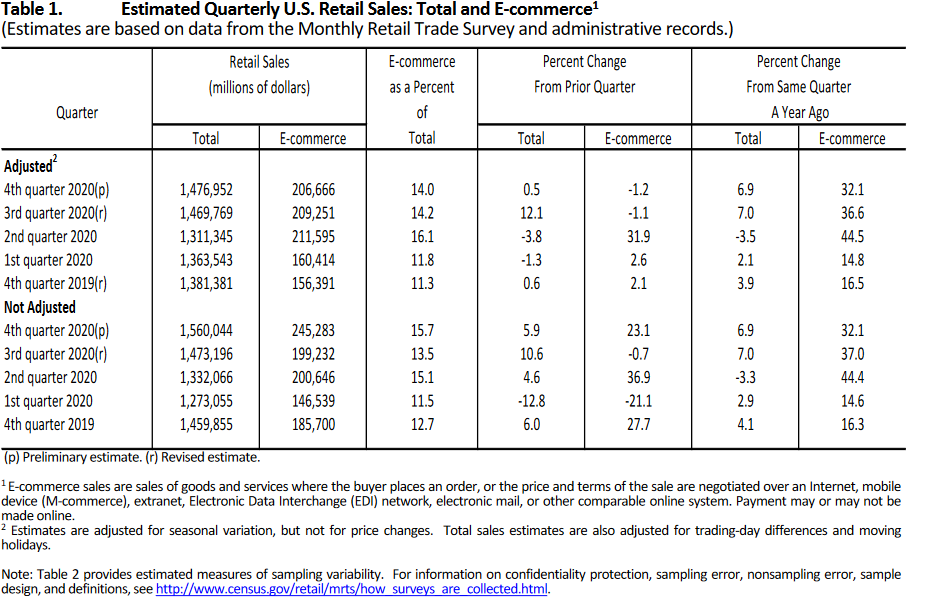

He also argued against the popular notion that e-commerce exploded during the worst of Covid-19. Online market share rose just 2% in 2020, he noted, proving that there could be a ceiling to consumer demand for shopping on the internet. He further noted that e-commerce sales figures include transactions where the consumer picks up the item at the store.

“I don”™t know about you,” he added, “but shopping for groceries online was a wholly frustrating and unsatisfying experience.” Likewise, Berne said he suspected that the nosedive seen in sales of apparel and shoes was not so much caused by the lack of need during the work-from-home era as it was by the preference for trying such items on in person.

“If retail was just about buying things we need in the most convenient way possible, it would not exist,” he declared, arguing that consumers have a “psychological need” to mix with other shoppers. “This notion that somehow e-commerce is going to be the way that we shop for everything ignores that psychology.”

Berne argued that relying entirely on e-commerce also does not work for most businesses, what with the costs of shipping “to everyone”™s doorstep,” customer acquisition and retention, and the “exorbitant advertising costs” on Facebook, Google and Amazon, and returns.

“That”™s just an unsustainable cost structure that virtually no one has been able to figure out how to make money on,” he said, noting that even Amazon showed an operating loss on e-commerce until 2019.

The “only way” e-commerce works, therefore, is in conjunction with brick-and-mortar stores via curbside pickup, a lower return rate ”” ¼ less than online, he said ”” and having a physical presence that can further improve the customer experience.

Downtowns are well-positioned against e-commerce, Berne said, as they have been accustomed to adaptive responses, whether it be to regional malls or online behemoths.

Still, he said a “new retail paradigm” could help further revitalize downtowns, with major anchor stores helping to support smaller mom-and-pops like pet supply and grooming stores, retail health care operations, boutique fitness businesses, and cannabis dispensaries.

Lowering barriers to entry, cultivating permanent tenants and providing a “sense of constant discovery” for visitors can also help downtowns “build back better,” Berne said.