Long before Amazon, there was Lillian Vernon

Along with Julia Child’s kitchen, the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C., is home to another culinary item, although one that was used to very different effect – foreshadowing Amazon, remote work and the rise of women entrepreneurs.

It was at her yellow Formica kitchen table in Mount Vernon in 1951 that Lilli Menasche Hochberg, a 24-year-old married woman pregnant with her first child, started what would become Lillian Vernon, an eponymous mail-order business featuring personalized items that at its height would see sales of $300 million and employ some 5,000 workers across Westchester County and several states. (Like the woman, the business would take its name from the city where it all began.)

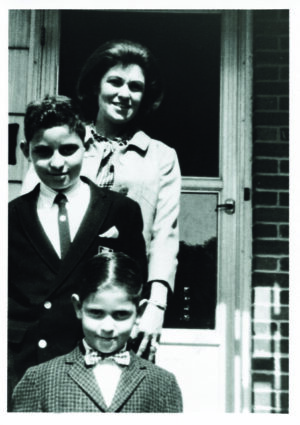

The kitchen table – along with almost 400 archival items donated by sons Fred P. Hochberg and David Hochberg, including a girl’s monogrammed purse and belt and a scrapbook Vernon kept as a teenager – went on view Oct. 17 in the Consumer Era (1940s–1970s) section of the museum’s “American Enterprise” exhibit in the Mars Hall of American Business. (The exhibit opened 86 years to the day that Vernon arrived in the United States as a Jewish refugee.)

The collection is not the Smithsonian’s only Vernon holdings: Enid Cutler’s pensive, Henri Matisse-like portrait of the entrepreneur (circa 1970, oil on canvas) is part of the National Portrait Gallery.

“The Smithsonian is the national museum of America,” said David Hochberg, who served as vice president of communications at the Lillian Vernon Corp. with older brother Fred as president and COO. “To be in those two museums is the ultimate honor.”

They are fitting honors for a woman who had a well-manicured finger on the pulse of what consumers, especially women, wanted. (She once bought – and sold – 100,000 bobbin candle holders.)

“She was her customer,” said David Hochberg, now an artists’ agent who lives part-time in Katonah.

An eye for what sells

As with all success stories, fulfilling Vernon’s business dream took some doing. She was born on March 18, 1927, in Leipzig, a German manufacturing and cultural hub, to Hermann Menasche – a prosperous lingerie manufacturer whom Vernon would describe in her autobiography, “An Eye for Winners,” as an elegant, exceptionally intelligent problem-solver; and his wife, Erna Feiner Menasche, a cool, fashionable beauty who came from a family of Belgian diamond merchants. Theirs was a happy home of dinner and ice-skating parties at the brick villa of their estate. But when the Nazis came to power in 1933, they confiscated the villa for a headquarters. Two years later, Vernon’s brother, Fred, was attacked by an anti-Semitic mob, and the family knew they had to get out. But where to go? First, they immigrated to Amsterdam and then – after considering Cuba and Palestine, David Hochberg said – the United States.

Vernon was 10 when the family arrived in New York City on Oct. 17, 1937. There her father found moderate success as a manufacturer of small leather goods. Everyone in the family helped with the business, with Vernon in particular developing a keen eye and sixth sense for the luxury goods her father copied. Like many immigrants, she was also quick to assimilate, claiming that “Hollywood was my Berlitz (school of languages),” because she perfected her English while watching movies as an usherette. During World War II, Vernon joined a Women’s Auxiliary Canteen. (Brother Fred, part of the U.S. Army’s Medical Corps, would die in a grenade attack during the Allied invasion of Normandy, which began on June 6, 1944.)

After the war, she attended New York University for two years – studying psychology and home economics — before marrying Samuel Hochberg, who worked in his family’s dry goods store. What she really wanted to do, David Hochberg said, was start her own business. It was not her husband’s dream, nor was he enamored of her using the $2,000 cash (almost $26,000 today) that was among their wedding gifts as seed money for her start-up. But Vernon believed that there was a female clientele – particularly a young, female clientele, now a powerhouse demographic, then an emerging market – for goods with free personalization.

Her husband agreed to join her venture – should sales exceed $100,000 – which they soon would. Vernon launched what was then the Vernon Specialties Co. with an advertisement in Seventeen magazine for personalized belts and purses that her father would make. The overwhelming response led to the Lillian Vernon Catalog (1956); the couple’s handmade jewelry; incorporation as Vernon Products Inc. in 1960 – it would become the Lillian Vernon Corp. in 1965 — and distribution deals with Revlon, Elizabeth Arden, Max Factor and Maybelline to follow.

Even the couple’s 1969 divorce didn’t slow her down, as Vernon ventured into the global marketplace, traveling to European fairs and, after President Richard M. Nixon’s 1972 overture, to China in 1980. She expanded with The New Co., a brass manufacturer; Provender, a wholesale division for toiletries, specialty foods and kitchen supplies; and catalogs for children and homemakers. With son Fred – who joined the company in 1975 after earning a Bachelor of Arts degree at NYU and an MBA at Columbia Business School — the Lillian Vernon Corp. grew 40-fold, with several locations in Westchester and other states, including the headquarters in Mount Vernon, a warehouse in New Rochelle and an outlet in Yonkers.

As Fred Hochberg – a part-time Greenwich resident who would serve as chair and president of the Export-Import Bank under President Barack Obama – recalled: “When I joined Lillian Vernon, the company did about $4.5 million in sales. By 1993, (when he left for investing and public service), sales were approaching $200 million. Sales grew by offering more unique and exclusive products to customers, increasing the customer base, and more targeted marketing.”

In 1987, he oversaw the consolidation of five facilities in Westchester into a 500,000-square-foot distribution center on 51 acres in Virginia Beach, Virginia, “to handle the company’s rapid growth and provide superior customer service.” That was an important year in another regard: The company went public on the American Stock Exchange. That initial public offering (IPO), underwritten by Goldman Sachs, would mark the first time a company founded by a woman was traded on the exchange.

The secret sauce

The secrets to its and her success? “She had tremendous drive,” David Hochberg said. As a boss, she was tough and demanding, he added, but generous and unpretentious, less concerned with her employees’ pedigrees and more interested in what they could learn and do. Even to this day, he added, people who worked for her come up to him to say she was the best boss they ever had.

Vernon was also a shrewd judge of character as well as merchandise and, in contrast to an age when every day seems to be Casual Friday, looked like the CEO she was in Chanel suits, her hair immaculately coiffed. (After a second marriage to engineer Robert Katz, she married hair salon owner Paolo Martino, the couple dividing their time between Greenwich, where they gave themed parties, and a Manhattan apartment with spectacular views of the East River.)

Though the company established an online storefront on AOL in 1995 and then an online catalog and website, it struggled in the digital age, and Vernon sold it to Zelnick Media in 2003, staying on as non-executive chair. After changing hands several times, the company was sold in 2015 to Regent LP, a multisector private equity firm in Beverly Hills, with the business still operating at lillianvernon.com.

That was just two months before Vernon died, on Dec. 14, 2015, in Manhattan. She left a legacy that went beyond business, however – serving on the boards of NYU, Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, the American Friends of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra and Citymeals on Wheels; supporting organizations throughout the country through the Lillian Vernon Foundation; and donating the West Village building that became NYU’s Lillian Vernon Creative Writing House. The Women’s Enterprise Development Council (WEDC) established the Lillian Vernon Awards to honor businesswomen who also excel at service to community. (See sidebar.)

But those of us of a certain vintage will remember Vernon as a pioneering woman entrepreneur who gave consumers the products they wanted – and let them, through the free personalization that continues to this day, truly make them their own.

Lillian Vernon’s commitment to entrepreneurship and service continues

In a nod to the legacy of the late Lillian Vernon, the White Plains- and Poughkeepsie-based Women’s Enterprise Development Center (WEDC) named Filomena Fanelli, founding CEO of Impact PR & Communications in Poughkeepsie, and Amy Hall, owner of Hudson Valley Books for Humanity in Ossining, as its 2023 Lillian Vernon Awards winners on Nov. 9 in Peekskill.

Vernon’s son David Hochberg was on hand to present the awards, alongside WEDC CEO Nikki A. Hahn. As part of the event, attendees were invited to bring entrepreneur- or business-related books to donate to WEDC’s Lillian Vernon Business Lending Library, which equips WEDC program participants with resources.

“Each year we recognize women business owners who, like my mother, know that true success means giving back generously to your community,” Hochberg said. “Filomena and Amy embody that spirit.”

“Both honorees show that it’s possible to innovate as entrepreneurs while also paying it forward and empowering others,” Hahn said. “WEDC is happy to shine the spotlight on Filomena and Amy and the sizeable impact they’ve had in the Mid-Hudson Valley, Westchester and well beyond.”

The Lillian Vernon Award was named for Vernon as its first recipient.