When photography became an art

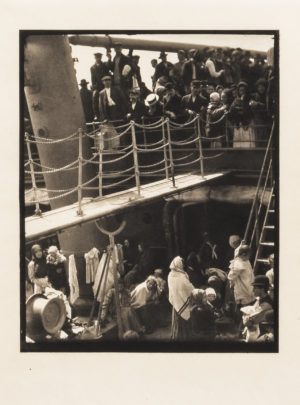

To be sold Jan. 16. Photograph courtesy Bonhams Skinner.

In the world of fine art, photography is a new kid on the block (and certainly photographs are relative newcomers on the auction block). The first fixed photographic images were made in the 1820s by the French pioneer cameraman Nicéphore Nièpce. His associate Louis Daguerre went on to develop the process called daguerreotype, which made photographs popular and affordable.

For the next 100 years, there was a persistent attitude that photography was a clever mechanical process rather than a serious form of artistic expression. Most major museums didn”™t have departments dedicated to photography until late in the 20th century. (In Manhattan, the Museum of Modern Art”™s was founded in 1940; The Metropolitan Museum of Art”™s, in 1992.) Few art galleries held exhibitions of photographs.

Early photography required patience, cumbersome equipment and specialized technical knowledge. By the late 1800s, however, the process started to be democratized. In 1888, Kodak marketed its first camera. It allowed anyone to press a button, take a picture and turn the process of developing the image over to a professional technician. And you could have multiple copies at an affordable price.

Photographic images were regarded as a useful and convenient way of preserving certain kinds of information, such as a great public event or a private record of how handsome a young couple looked on their wedding day. Artistic goals such as creativity, self-expression and even social commentary weren”™t perceived as possible or even legitimate goals of “taking a picture.”

Around 1900, attitudes started to change. Alongside the growing popularity of the amateur snapshot, photography as a fine art gained growing recognition. The same schools that flourished in painting ”“ Pictorialism, Tonalism, Realism and Modernism ”“ were explored by men and women using increasingly sophisticated tools and techniques.

Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946) was a towering giant in the evolution of photography from a trade or a hobby to a fine art form. As well as an accomplished and prolific photographer himself, he had enormous influence as a mentor, writer and gallery owner. In addition, from 1897 to 1917 he was the editor of Camera Notes and Camera Work, at the time the best photographic publications in the world.

Stieglitz”™ Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession ”“ later called 291 for the gallery”™s location at 291 Fifth Ave. in Manhattan from 1905 to ”™17””started out by featuring the work of Edward Steichen, Clarence H. White, Gertrude Käsebier and Alvin Langdon Coburn. As the increasingly well-known Stieglitz gallery evolved, he exhibited photographic images alongside paintings and drawings by important contemporary artists, reinforcing his goal of establishing photography as a fine art form. (It was a goal that he continued pursuing in the next chapter of his life as he developed a professional and personal relationship with painter Georgia O”™Keeffe.)

Collectors today continue to seek out the works by Stieglitz and his contemporaries that fascinated collectors in the early 20th century. In addition to the Photo-Secessionists, art photographs by Ansel Adams, Alfred Eisenstaedt and Edward Weston and other modern masters are featured in Bonhams Skinner”™s periodic fine photography sales. One such auction will take place in January, with previews available in the Boston and Marlborough, Massachusetts, galleries.

If you want to add to your own collection of this recent fine art form, or you have fine photographs to consider consigning for sale, contact James Leighton (james.leighton@bonhamsskinnerinc.com). A picture is not only worth a thousand words; it may be worth thousands of dollars.

Contact Katie at katie.whittle@bonhamsskinner.com or 212-787-1114.