His labors grew a law firm

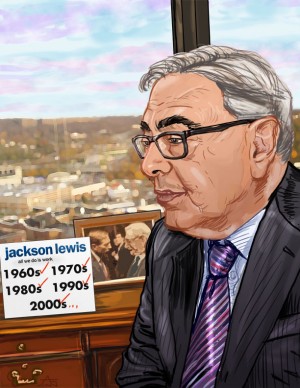

Patrick L. Vaccaro is at his desk in his 15th-floor corner office at Jackson Lewis L.L.P. with a panoramic view over downtown White Plains. He is reminiscing, about career and family, decisions made and risks taken, with a visitor and an old friend and colleague. Prominent behind his desk is a framed photo of Vaccaro chatting with Gen. David Petraeus at the scandal-ensnared military leader”™s confirmation as CIA director.

“We were talking about ties,” says the 73-year-old Vaccaro, who steps down at the end of this month as national managing partner at Jackson Lewis, having guided the labor and employment law firm through six impressively successful years. Petraeus didn”™t shop much for neckwear before his transition to civilian life. He liked the lawyer”™s tie.

“He was one of my strong idols ”“ and still is,” says Vaccaro, whose accent is a tough New Yorker”™s out of working-class New Rochelle.

Another idol of his, Ronald Reagan, beams from a photo frame on a side shelf. Two other conservative leaders of the western world, Winston Churchill and Margaret Thatcher, also rank in the lawyer”™s personal pantheon.

Add to that list Maurice Trotta, an author writing on labor issues, attorney and management professor who hired and mentored Vaccaro during his undergraduate years at New York University. Were it not for Trotta, Vaccaro might not be appending “Esquire” to his name. He might not have had the distinguished professional career that recently earned him induction in the New Rochelle High School Alumni Hall of Fame.

“I was pretty much set to go to NYU School of Business,” he recalls. “He directed me to go to law school.” All the key decisions on labor issues are going to be made by lawyers, Trotta advised. “I had no interest in law school.”

It showed in his law studies. “I hated it,” says Vaccaro, who had finished in the top 10 percent of his undergraduate class at NYU. “I was a terrible student.”

“There were no jobs in labor law when I got out of law school.” Labor litigation was rare and the chief employer of labor lawyers, the National Labor Relations Board, “had a freeze on,” Vaccaro remembers. “There was nothing.”

In Manhattan, “Jackson Lewis was one of the few firms at that time that was looking for young attorneys. They were looking to grow.” In 1966, Vaccaro was “the sixth or seventh or eighth” attorney to join the boutique firm.

“There were times that I didn”™t know I”™d have a job in those first four or five years. The five or six of us that worked under the partners literally knew every case that was in the firm. ”¦We would share work just to stay busy.”

Vaccaro”™s father was a union sheet metal worker and construction supervisor in New Rochelle who moonlighted as an amateur welterweight champion with a 48-times-delivered knockout punch. The son was raised in a household left financially bruised by occasional labor strikes.

“Those were some of the most painful times,” he says. “My dad was a very proud guy ”“ not much money coming in.” The son”™s career has been largely spent facing union reps across the table on behalf of employers.

In the early ”™80s, Vaccaro opened the firm”™s White Plains headquarters, where he was the office”™s managing partner for about 25 years. In 2006, he was unanimously named overall managing partner at Jackson Lewis, succeeding a partner who had held the top job for 30 years.

Vaccaro took over a firm with 21 offices and 369 largely homegrown attorneys. Jackson Lewis ended that year with $178.5 million in revenue.

Six years later, Vaccaro”™s aggressive strategy to grow the firm by hiring partners laterally from other law firms around the country has borne profitable results. While many firms have closed their doors or downsized in the recession, Jackson Lewis has expanded to include 49 offices and 735 attorneys. The firm”™s projected revenue for 2012 is $353 million, a 98 percent increase from Vaccaro”™s first year in the managing partner”™s job.

Jackson Lewis has incurred no debt in its Vaccaro-driven expansion. “Our growth is paid for from our revenue,” he says.

Bringing “laterals” into a firm”™s distinctive culture is, like marriage, a risky undertaking, says Vaccaro. “You don”™t know until you marry them.”

“It”™s very collaborative. We share clients. We share credits. We don”™t eat what we kill, we spread it around. ”¦There are no Lone Rangers in this firm.”

At most firms, “I”™d be making three to four times more than I am making” for having led such marked growth, Vaccaro says. “I don”™t make a lot more money” than before he took the top job. “We are a very flat compensation firm. Our compensation is very compressed. We don”™t have any pigs at the top.”

Vaccaro functions at the top as the firm”™s day-to-day troubleshooter and problem solver. On the previous day, he had driven to the firm”™s 42-attorney office in Morristown, N.J., to plan a partner”™s move to the managing partner position in the Philadelphia office. The busy New Jersey office will lose a valuable attorney, “but it was more important to get some stability in there in Philadelphia,” he says.

Dropping in at regional offices as the firm”™s oft-traveling overseer, “It”™s just, how do we do better at what we”™re doing? We try to shake things out and see how things are going. ”¦We”™re like 49 movable parts that come together for the whole.”

“I don”™t travel as much as I used to,” says Vaccaro. “When I was managing this office, it was three or four days a week. That I would not want to do again.”

The top management job keeps him from practicing in the complex field of labor and employment law. “This is a full-time job,” he says. “This firm, 750 attorneys in 49 offices, is too much to do on a casual basis.”

“Being managing partner is not an awful lot of fun. Practicing law is fun. The real fun in being a lawyer is lawyering. I never went to law school to be an administrator. But here I am.”

Vaccaro won”™t give up the corner office on Jan. 1, when he hands the managing partner”™s job and its “aggravation” to his firm”™s national litigation director in Morristown, Vincent Cino. “He will rely very heavily on me, I know he will,” says Vaccaro, “to help him with the day-to-day stuff.” Vaccaro will focus on marketing.

“Pat is at his core a marketer, a business developer,” says Clare Grossman, the longtime marketing director at Jackson Lewis and Vaccaro”™s old friend.

“I”™m going to stay on another four years, possibly five years. After that, I think that will be it for me,” says the master at Jackson Lewis.