Motives for doctor payments examined

As more light is shed on drug company payments to physicians, national trends show payments decreasing. But in Connecticut, it”™s more of a mixed bag.

From 2009 to 2012, pharmaceutical companies paid Connecticut doctors at least $28 million for conducting clinical trials, speaking at promotional lectures or attending dinners, according to an analysis by the Fairfield County Business Journal of publicly reported payments.

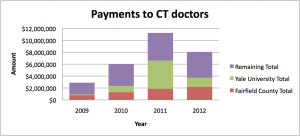

Payments to Connecticut doctors were on an upward trajectory ”” contrary to national trends ”” until 2012, when they decreased 28 percent, primarily because of a drop in research funding to Yale University.

More than 50 doctors in the state grossed at least $100,000 in payments from pharmaceutical firms from 2009 to 2012, with some earning as much as $1 million for research. In Fairfield County alone, nearly 500 doctors have been paid at least $250.

To report these findings, the Business Journal used data compiled by ProPublica, a nonprofit news organization. But the data have its limitations.

The 15 drug companies included in the data represent only 47 percent of the U.S. pharmaceutical market. Among the companies that disclosed payments, not all of them reported the same kinds of payments or reported payments for all four years. For instance, most companies reported how much they paid in speaker and consultant fees, but not every company reported how much they gave doctors for research, travel reimbursements, meals and educational gifts. As a result, the total amount of money paid to physicians nationwide is likely much higher than the $2 billion publicly reported over the last four years.

The payments are designed to compensate doctors for their time, whether it”™s for research or speaking at promotional events. Drug manufacturers say the two are vital to the progression of medicine and educating physicians about both the pros and cons of their drugs and how to safely prescribe them. Critics question the ethicality of the payments and whether they are influencing doctors to prescribe certain brands and medications over other treatments.

Dr. Joseph Ross, an assistant professor at Yale University School of Medicine, said he believes research and clinical trials are good examples of academic and industry cooperation. Multimillion-dollar research projects have to happen, he said. But what does worry him are the smaller payments, such as speaker fees, meals and travel reimbursements.

“What I care about is how these payments can influence the care for patients,” Ross said. “There”™s no reason a physician needs to be paid to hear about a promotion.”

Ross was a part of one of the first successful efforts to bring to light the issue of pharmaceutical company payments to doctors. In 2007, he was the lead author of a study covering the subject in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Now, under the Physician Payment Sunshine Act ”” a provision of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act ”” all drug companies will be required to collect payment data for public disclosure in 2014. A few states already require payment disclosure; however, Connecticut isn”™t among them.

“It”™s going to have a tremendous impact,” Ross said of the new regulations. “No more loopholes or considerations about what we don”™t know. There”™s just so much missing from the data. We”™ll finally have a comprehensive understanding.”

With more public disclosures and scrutiny over the data, Ross said he hopes more doctors will be dissuaded to accept payments for fear of the possible negative publicity.

In advance of the new legislation, payments to doctors have already begun decreasing nationwide, though it”™s difficult to say by how much, with more companies starting to report nationwide.

In Connecticut, it”™s also difficult to say with certainty why payment levels have seemed to both increase and decrease. In 2009, $2.8 million in payments were publically disclosed, but fewer companies were reporting then. By 2011, disclosed payments were as high $11.2 million, but in 2012, payments fell to $8 million, primarily because large research grants to Yale University appeared to have decreased. Yale officials declined to comment, noting they do not track payments, but require employees to disclose conflicts of interest.

Representatives at Pfizer Inc. say a nationwide decrease in its payments to physicians is primarily due to the company”™s changing drug portfolio that includes fewer patented drugs, which in turn don”™t require the same level of funding.

Additionally, the company says it is using more cost-effective tools to educate physicians, such as web conferences instead of dinners and events.

“We are utilizing more efficient and strategic ways to deliver educational material, and are evolving our approaches to meet physician information needs,” said Steve Danehy, a Pfizer spokesman, in an email. “To suggest anything otherwise would be an oversimplification of the data.”

Pfizer has publically disclosed its payments since the second half of 2009 as a reflection of its “unwavering” belief that its collaboration with doctors “led to meaningful and productive dialogue, scientific insights and improved medicines for patients.”

In Connecticut, Pfizer”™s payments made up 20 percent to 40 percent of disclosed payments every year from 2009 to 2012. The company is also a key reason why funding decreased dramatically in 2012, when it decreased its research funding to Yale.

Dr. Ghazi Asaad, a psychologist in Danbury, has made at least $222,100 in the past four years as a promotional speaker, according to the Business Journal”™s analysis.

Assad said he”™s been speaking at events since the 1990s, sometimes speaking as often as every week for four or five companies in a year. He doesn”™t keep track of how much money he”™s earned.

Asaad said he was aware of criticisms that drug companies were choosing doctors to be speakers based on how many patients they had, instead of their ability to speak well. But Asaad said he considers himself to be an excellent speaker who is not persuaded to prescribe the drugs he speaks about. He has about 2,000 patients.

Looking from the corporate point of view, Asaad said he thinks the companies are trying to influence speakers and those in attendance to prescribe their drugs.

“They want promotion, they want to sell drugs,” he said. “It”™s obvious. It”™s an open agenda. If they can manipulate the speaker to be biased, they will do it.”

But from the doctors”™ perspective, a simple event is not going to manipulate them. A free meal isn”™t either, he said.

“The drug companies try to be pushy, and to some degree, try to be unethical with some speakers, but I think it”™s all about the integrity of the speaker,” Asaad said. “Now I might be one of the top paid people but nobody can influence my prescribing habits. In fact, many times they become frustrated with me. They say, ”˜Why are you prescribing this drug instead of this?”™ And I say, ”˜Because that”™s what the patient needed. It works. It”™s more affordable. Why not?”™”

Dr. Joseph F. Goldberg, a psychiatrist in New Canaan, wasn”™t as liberal with his words. Goldberg, who has received at least $321,000 in four years, emphasized how the events help doctors learn about the proper use of the medications. All the materials and the events themselves are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

“I do not personally feel pressure to prescribe certain brands over others when multiple FDA-approved treatments exist for a particular ailment,” he said. “Such programs are meant to make attendees more familiar with the appropriate use of a treatment as they hopefully make their own independent decisions.”

Goldberg has conducted clinical research in psychopharmacology for more than 20 years and questioned why he shouldn”™t be paid for his time and expertise.

Asaad contends no doctors would speak if they weren”™t paid, but that if it was the money he was after, he could make much more by taking on additional patients. Asaad said he is a speaker primarily because it”™s a social activity and because he wants to help educate physicians about the drugs. The events are often the best way to learn about the side effects, safety precautions or how to prescribe certain drugs. Plus, the companies create a positive atmosphere that”™s very pleasant, he said.

“This is business in America, this is how business goes,” Asaad said, noting that other industries might take clients to Las Vegas or give them private jets. “Our judges are our patients. I think they see if people are good or not good. And I can assure you they have not said a word.”