New York Medical College founder ‘comes home’

A portrait of one of New York”™s early movers and shakers has “come home” to New York Medical College in Valhalla, shedding light on a once prominent artist in the process.

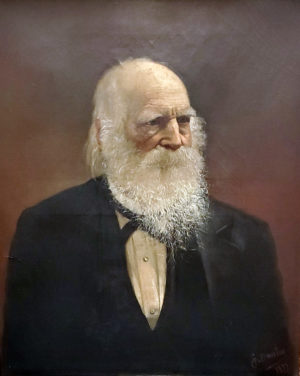

Ferdinand Danton Sr.”™s “Portrait of William Cullen Bryant” (1877, oil on canvas) has gone on display in the lobby of the college”™s Medical Education Center. The portrait depicts Bryant (1794-1878) ”“ poet, editor, abolitionist and the most prominent founder of the medical college ”“ as a literary lion in winter, his grizzled, snowy-white beard a contrast to his black suit and the sepia backdrop. The work was a January gift from medical college alumnus Jay D. Tartell, M.D., (Class of 1982).

“William Cullen Bryant’s often forgotten contributions to the ascent of America and the vitality of New York need to be understood and remembered today,” Tartell , a radiologist, said in a statement. “Bryant’s role in the founding of New York Medical College is of obvious interest to the college community. But his role as a ”˜Renaissance Man,”™ advancing our country on multiple fronts ”“ including science, art, politics, literature, world awareness and moral”¯principles ”“ can serve as an even greater inspiration to our students.”

Edward C. Halperin, M.D., M.A., the medical college”™s chancellor and CEO, elaborated on this in another statement:

“William Cullen Bryant thought the great oppressors of Americans were racism, sexism, alcoholism and income inequality. He had a four-pronged solution to this four-pronged problem ”“ emancipate all enslaved people and grant them the vote, women”™s suffrage, temperance and allowing workers to form trade unions and collectively bargain with management. These were very progressive views for the 1850s and1860s. But these views helped create the institutional culture of New York Medical College when he founded it in 1860.

“We are proud to acknowledge our heritage and have this portrait of our founder ”˜back home.”™”

Born near Cummington, Massachusetts, Bryant came to early literary prominence with his poem “Thanatopsis” (1817), arriving in New York eight years later. As editor and subsequent owner of the New York Evening Post, he championed progressive causes as well as the Hudson River School of landscape painting, a group of artists that would define the United States as the new Eden in the period that bracketed the Civil War. On Feb. 27, 1860, Bryant introduced a relatively unknown Republican presidential candidate from Illinois in his first public address in New York City, at Cooper Union. Abraham Lincoln would later say that that speech in New York, in which he argued that there could be no middle ground in rejecting slavery, helped make him president of the United States.

Less than two months later on April 12, the founding charter of New York Medical College was approved by the New York Legislature. A supporter of the college, Bryant assumed the presidency of its board of trustees in 1862, a position he held until his death in 1878. As a New York civic leader, Bryant also played key roles in the establishment of Central Park, The Metropolitan Museum of Art and New York Medical College-affiliated Metropolitan Hospital.

The Bryant painting also sheds light on Danton, a little-known artist who was prominent in his day, said Nicholas Webb, archivist and digital preservation librarian at the medical college”™s Phillip Capozzi, M.D., Library, where he is responsible for curating the library”™s historical collections and providing research and reference services regarding the college”™s rich history.

A descendant of French Revolutionary leader Georges Danton, Ferdinand Sr. (1850-1912) was born in France and studied painting in Paris before emigrating to the United States in 1869. He was sought after for his paintings for Roman Catholic churches in upper Manhattan, Webb said, as well as his portraits of 19th-century luminaries ”“ including John L. Sullivan, the first heavyweight champion of gloved boxing, who didn”™t like Ferdinand Sr.”™s resulting work and sued him to get his money back. In 1905, Ferdinand Sr. became founding chairman of the Department of Art at Fordham University in the Bronx.

Webb, who became something of a detective to discover more about Ferdinand Sr., said that Ferdinand Jr. (1877-1939) is better known today and with good reason: This painter of landscapes, portraits and trompe l”™oeil still lifes of paper currency was primarily a forger, who was imprisoned and died penniless.

He did add, however, “This painting is an excellent example of one of many portraits and memorial items created”¯to honor Bryant near the end of his life. One other notable example of such works is the beautiful commemorative vase commissioned by a group of Bryant’s friends for his 80th birthday.”

Designed by James Horton Whitehouse with medallions by Augustus Saint-Gaudens and relief work chased (heightened) by Eugene J. Soligny, the silver and gold amphora ”“ which mixes elements of the Renaissance Revival and Aesthetic styles ”“ was manufactured by Tiffany & Co., displayed at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876 and presented to The Metropolitan Museum of Art the following year. It was The Met”™s first acquisition in American silver ”“ a fitting tribute to a sterling figure in the nation”™s history.

For more, visit nymc.edu.