In November, Greenburgh Town Supervisor Paul Feiner announced on Facebook that the town had just installed solar panels on the roof of town hall, eliciting dozens of “likes” and a presentation at the next board meeting. He joined nearly every other mayor and public official in New York state advertising their efforts to reduce our reliance on fossil fuels. But while solar power undeniably serves a public good, its efficiency pales in comparison to a simpler but much bolder project that has languished in the regulatory process for nearly seven years.

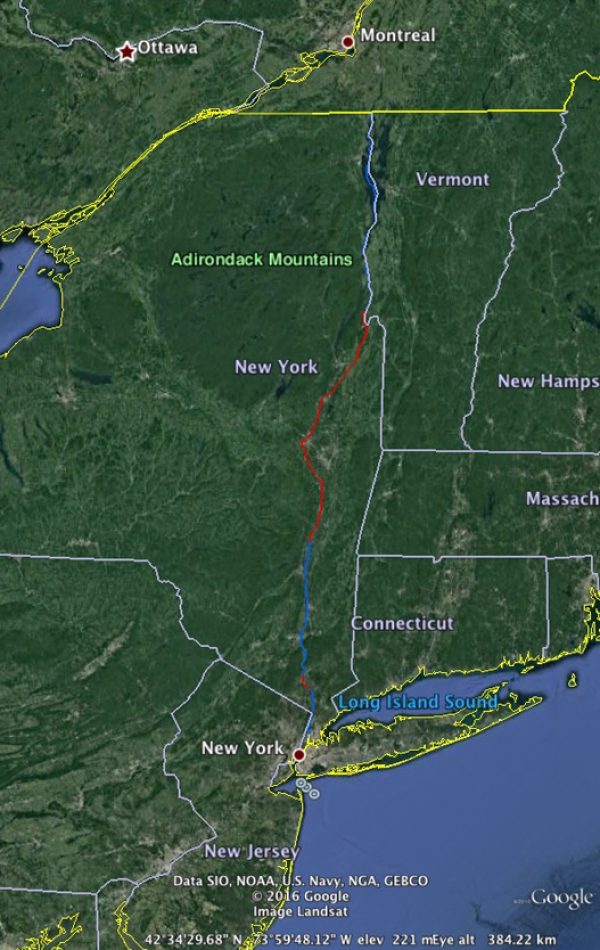

It”™s called the Champlain Hudson Power Express (CHPE), a high-voltage direct current transmission system that would take 1,000 megawatts of clean, renewable hydropower from northern Quebec and bring it into the New York  metropolitan area grid. The transmission line would stretch for 333 miles from Canada to a New York City substation in Astoria, Queens. It would transmit the hydropower via two buried copper cables, six inches in diameter, essentially an extremely long power cord no different from the one used by your toaster.

metropolitan area grid. The transmission line would stretch for 333 miles from Canada to a New York City substation in Astoria, Queens. It would transmit the hydropower via two buried copper cables, six inches in diameter, essentially an extremely long power cord no different from the one used by your toaster.

While it”™s not sexy, it will bring an enormous quantity of nonpolluting electricity to the city and surrounding counties, such as Westchester, Rockland and Long Island, and shave $500 million dollars a year off the cost of wholesale power to ratepayers, according to studies accepted by the Public Service Commission.

The line will be buried for its full length underground and under the Hudson River in a trench no more than six feet wide and four feet deep in most places. You would think it should be relatively simple to examine the environmental impacts of essentially digging a hole, adding two cables and then covering it up, but it has been wending its way through the state and federal government”™s byzantine approvals process since 2010.

Champlain Hudson Power Express vs. solar power

Let”™s compare the value of CHPE to solar power in New York state.

According to the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, ratepayers have already shelled out $527 million to develop 51,000 residential and nonresidential solar power projects totaling 669 megawatts. The capital funding for these projects came from taxes labeled as charges on our electricity bills, primarily the system benefits charge.

Privately funded, the $2.5- billion CHPE project will cost the ratepayers nothing to build. At 1,000 megawatts, its capacity is nearly 50 percent larger than all solar installations combined. But there”™s an even bigger payoff in the number of kilowatt hours produced because while solar panels can generate electricity only during daylight hours when the sun shines””five hours per day in New York on average – the hydro turbines run 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Thus, a megawatt of solar power produces about one-fifth (5/24) of the amount of electricity a megawatt of hydro generates.

Just like solar, once the infrastructure is built, the “fuel”””water from Quebec”™s La Romaine River””is freely available forever. The Public Service Commission and other experts conservatively estimate the savings in the wholesale price of electricity at over $500 million dollars a year to New York City, Westchester and other metro area ratepayers. The environmental benefit includes the annual savings of over 2 million tons of carbon dioxide compared with fossil fuels.

Expansion of solar power undoubtedly makes sense as a response to global warming and the state”™s challenge to wean itself from fossil fuels. But we must also find the means to implement more cost-effective solutions, such as the CHPE, so they don”™t face a regulatory gauntlet that discourages innovation.

The bureaucratic nightmare of permitting

There are three major problems with approvals for development projects in New York state. First, agencies with jurisdiction rarely coordinate their reviews. Second, they do not recognize that time is money. And third, the court system is so congested that challenges take too long to adjudicate. All of this leads to uncertainty and failure for many worthwhile projects whose developers either don”™t try or go bankrupt before they reach the finish line. Approvals delayed are approvals denied.

Agencies and boards should coordinate their reviews

It”™s not that we don”™t know how to move projects. Strong leaders have traditionally found ways to smash through the bureaucracy. Gov. Andrew Cuomo took a decade-old effort to replace the Tappan Zee Bridge, redesigned the permitting process to enable agencies to study it concurrently and rammed it through in record time. In Westchester County, using a generic environmental impact statement for the downtown, Mayor Noam Bramson streamlined the SEQRA (NYS Environmental Quality Review Act) process, enabling a $4-billion transformation of New Rochelle”™s downtown. Yonkers Mayor Michael Spano launched what he calls a “concierge” permitting process for his downtown, in which all of the permitting boards coordinate with each other to insure concurrent rather than consecutive consideration, with one board”™s approval sometimes contingent upon another”™s.

But these examples are exceptions, as most local communities use home rule to thwart any development proposals with which they disagree, using developers”™ own money against them. Coordinated consideration of projects should be standard and not dependent on strong individual mayors or governors.

Instead of collaboratively studying the CHPE, four different approving agencies, each with its own procedures, looked at essentially the same issues. Ironically, the first of those agencies, the New York Public Service Commission (PSC), did a fine job with the first major approval. After the CHPE developer spent millions of dollars and two years of studies to design the project and consider its impact, staff of the PSC helped hammer out a joint agreement with 21 interested parties.

While it took two years and 50 settlement conferences to satisfy disparate interests, such as the state Department of Environmental Conservation, the city of New York, Riverkeeper, the Adirondack Park Agency and even the New York State Council of Trout Unlimited, any one of them could have sued and tied up the project for years. After public hearings, the PSC issued its certification one year later in April 2013.

In a preface to the 621-page approval decision, the PSC wrote: “The fact that so many parties, representing myriad interests and advocating a broad spectrum of concerns, could reach agreement on so many detailed, technical and policy-based issues is a remarkable achievement and is consistent with our settlement rules.”

The PSC”™s coordinated review should have ended with a shovel in the ground in April 2013. But because of authorizations required from the U.S. Department of Energy, Army Corps of Engineers, and Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, nearly four years have gone by, costing ratepayers about $2 billion in lost savings.

Introduce the concept that “time is money”

Of course, the regulatory process should allow everyone to be heard. But since the permitting bureaucracy faces no legal time constraints and guidelines are regularly broken, no one is held accountable for delays.

Business uses critical path analysis and Gantt charts in project management and so should government. All tasks to accomplish a project are placed on a timeline and organized based on which are dependent and which are independent. For example, studying the environmental impact of a project is dependent on first designing it.

All of the tasks required for approval from all agencies should be placed on a master task list and then organized on a timeline to determine task order for maximum efficiency. Once the timeline is developed, the bureaucracy should commit to estimated dates, which may be adjusted as the project moves through the process. This will have the added benefit of introducing accountability for time delays by government bureaucrats.

Limit the lawsuit lottery

The court system is so clogged with frivolous litigation that opponents know they can delay a project for virtually any reason for little money. Delays could be reduced with an investment of resources into the courts so that lawsuits are considered in a timely fashion. Judges who sit on decisions should be held accountable and would if they were monitored.

The developers of the Champlain Hudson Power Express are not complaining about the time it has taken for their $2.5 billion project. After seven years, they have completed all but one major hurdle, with construction projected for the middle of 2017.

But we can do better.

Legislation is needed

The New York State Legislature should draft a Concurrent Review and Approvals Act that would mandate that all permitting agencies and boards meet jointly at a scoping session at the inception of a qualified project, determine the most efficient way to consider it using critical path analysis and a Gantt chart, and commit to estimated timeframes to insure transparency and accountability. Until such an act is passed, jurisdictions could voluntarily adopt these approval practices ”“ collaborative scoping, timeline with Gantt chart and concurrent review – and developers could ask for them as a condition of their investment.

In sum, we can continue playing small ball, spending a trillion dollars to fix potholes, or re-engineer our regulatory process to encourage bold private initiatives that can lead to a more prosperous and sustainable society. We can no longer afford to ask the agents of growth to risk millions of dollars in an uncertain and highly litigious regulatory environment, or go somewhere else. It”™s time now to re-engineer the regulatory process for growth.

Alexander Roberts is executive director of the fair housing group Community Housing Innovations Inc., headquartered in White Plains. Contact him at aroberts@chigrants.org or 914-683-1010.